As soon as we see Edward G. Robinson in The Woman in the Window, we know there’s going to be trouble. He’ a professor of psychology (a fact that is helpfully driven home by the name “SIGMUND FREUD” on the chalkboard behind him, even though nothing he’s saying has anything to do with Freudianism), and he’s delivering a lecture to his students on how, the Fifth Commandment notwithstanding, there is murder, and then again, there is murder. In a crime film, this means the question isn’t if he’ll get mixed up in a homicide, but when, and how many.

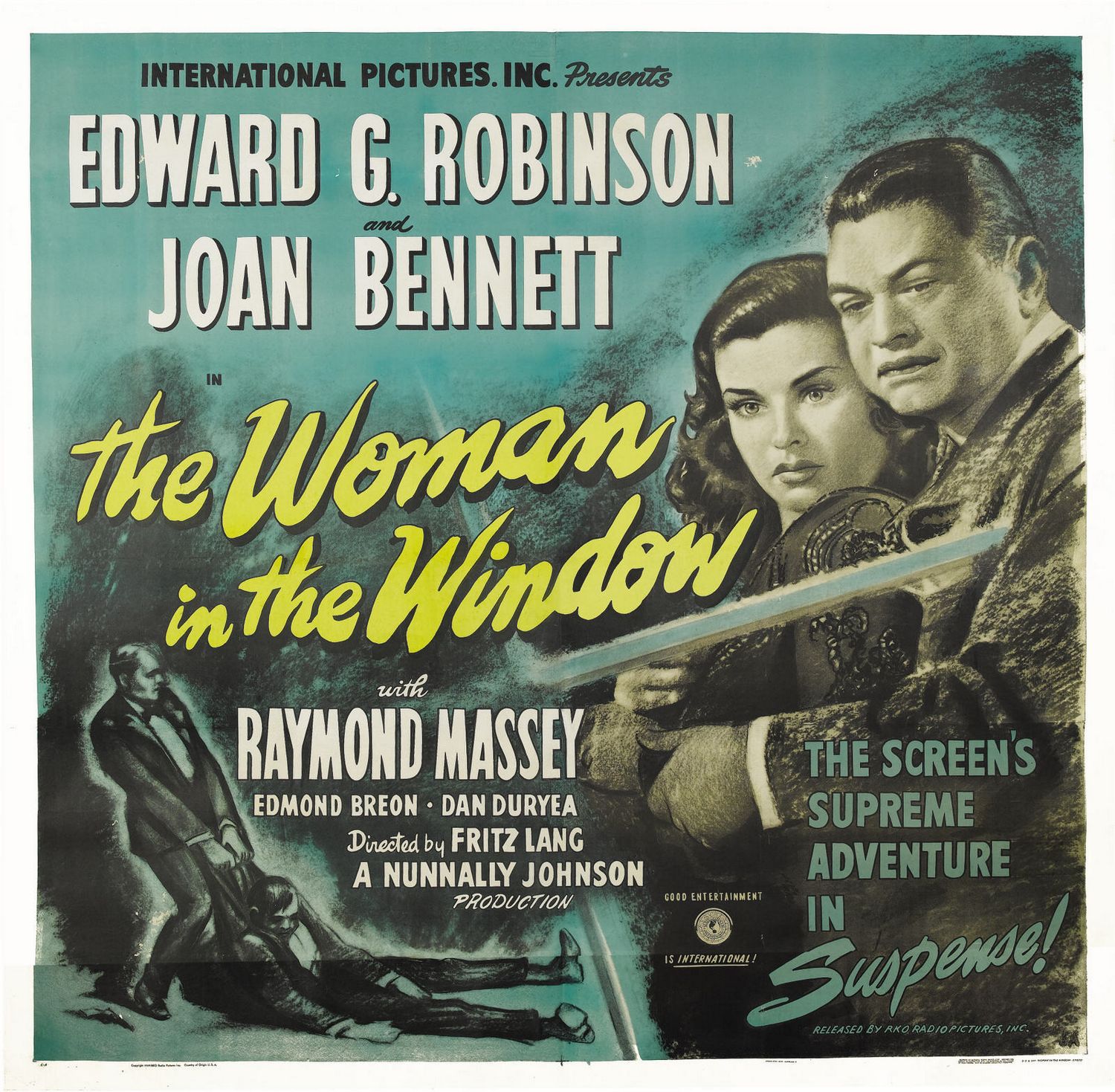

After seeing his wife (who looks pretty much like you’d expect someone married to a guy who looks like Edward G. Robinson to look) and kids off to their summer getaway, Robinson hangs out with some colleagues, and they bond rather creepily over a storefront portrait of Joan Bennett. The three of them smoke cigars, get tight on brandies, and lament over the fact that they’re all three a bunch of decaying blobs who can’t rate with the young girls anymore. Raymond Massey, playing the district attorney, vapors on about how he’s seen plenty of misery come from guys who can’t keep it in their pants around the young stuff, but Robinson isn’t having any of it. Instead of going out and buying a sports car like a normal middle-aged Lothario, he allows himself to get all het up by reading Song of Solomon, hands down the Bible’s smuttiest book, and wanders off to gape at the foxy painting of Joan Bennett.

Unfortunately for him, but fortunately for the plot, Bennett herself is lying in wait, and soon enough the two are flirting over cocktails. She invites Robinson back to her place to look at some etchings — no, really — and we’re off to the races. (Bennett is pretty flat throughout the movie, but when Robinson bristles at visiting the apartment of a beautiful young woman he’s just met by meekly saying “I don’t think I should”, her response — “You don’t think you should?” — is a perfect mixture of coaxing and flat-out mockery.) No sooner are they back at her luxurious modernist pad than her sugar daddy, played by Arthur Loft, barges in, smacks her down, and starts to choke the life out of presumed cuckolder Robinson; during the struggle, Bennett hands Robinson a pair of scissors, and he stabs Loft to death in self-defense.

Robinson is more concerned about his reputation than the actual killing, and that’s what drives the Hitchcockian innocent-man-makes-one-small-mistake plot into high gear. He decides to enact a plan to dump the body and hope that no one can connect the murder to him or the all-too-willing Bennett; this process is fraught with complications (including a drive in which he encounters every cop in the tri-state area, worst of which is a traffic cop who grins unnervingly at him at a red light) and leaves plenty of evidence behind for D.A. Massey, who is as expert at the practice of homicide as Robinson is as its theory. Their head-butting takes up a good portion of The Woman in the Window’s middle passage, and it lets a lot of the air out of the film, since Massey reads his lines like he’s late for dinner and Robinson’s character lacks the internal conflict and sense of moral compromise that marks the best noir protagonists.

The later passages pick up a bit, largely thanks to the appearance of two characters that lively up the movie considerably: Thomas E. Jackson as the lead detective investigating the case (he has the look of a hungry vulture when he sizes up Robinson and tells him that the police department’s most valuable asset is patience) and Dan Duryea as a blackmailing sleazeball who was the victim’s bodyguard. Duryea finally turns on the heat in The Woman in the Window with his typically energetic performance as an insinuating brute, and his arrival also marks the return of Bennett, who shows up with a nice little twist that gets the movie going again. Things get progressively worse for Robinson, until it all comes to a head in the film’s somewhat infamous ending, which reeks of the Hays Office but which was supported by director Fritz Lang himself.

The Woman in the Window is chock-full of historical curiosities, not the least of which is the fact that it accompanied a wave of mid-’40s crime dramas released in France after the war that gave rise to the term “film noir”. It was also the first film by Independent Releasing, the studio founded by Nunnally Johnson, who got rich working with John Ford and wanted to make his own movies; he picked Lang to direct it, which sets up one of its weirder aspects: it features the exact same cast (Robinson, Bennett and Duryea) as Lang’s Scarlet Street, which came out a year later and also has amateur portraiture as a plot hook. The best way to tell the difference between the two is that, well, Scarlet Street is a quite a lot better. Finally, its tacky ending — which, from any other outfit, would seem like the result of studio nervousness — is one of the last such examples in American crime drama before the big noir pushback of the post-war era; Johnson (who produced and wrote the screenplay) and Lang do the best they can with it, but even taking the tenor of the times into account, it’s still the movie’s biggest black mark.

The merits of the film are largely visual. Bennett and Massey rise as far as perfunctory with their performances, and while Duryea is plenty juicy when he finally shows up and Robinson is his usual competent self (getting better when he’s required to act, post-homicide, like all the life has been sucked out of him), there’s not any stellar acting going on here. The plot is solid enough, but it never allows itself to get down and dirty the way the best noir films must; one way that Scarlet Street, despite a similar story and theme, is far superior is that it lets its emotional tenor get way out of whack, conveying Robinson’s sense of sexual desperation and helplessness and Bennett and Duryea’s contemptuous manipulation, in a much more deep and effective way. The Woman in the Window never lets itself go like that, and the result is a movie that doesn’t have many troughs, but also lacks any real peak.

Lang, though, can’t help but let his amazing eye for lighting and composition come through; along with journeyman cameraman Milt Krasner, he sets up some fine scenes, especially early in the film. When Robinson and Bennett first visit the apartment, she walks through, clicking on one light after another, illuminating each section in a way that’s both seductive and menacing. After the murder, Lang pulls the camera way back and has Bennett hunch in the farthest corner, making her look like a humiliated schoolgirl — a move that conveys more than her acting does. In fact, this is The Woman in the Window‘s biggest problem: Lang’s direction is always writing checks that Johnson’s script can’t cash. The framing, staging and camerawork — of Robinson clumsily hanging up a phone, cowering rain-soaked in a darkened foyer, or dragging a corpse down a stairwell that looks like a tunnel to Hades — are all superior to the awkward bits of exposition, the plain script, and the arbitrary complications. (There’s also a few shots of Loft’s corpse — eyes wide open and lit with a bright spot to the face — that are more chilling than anything else in the movie.) Though there are some decent bits of dialogue, including one of my all-time favorite noir lines (“She’s got something on her conscience, but what woman doesn’t?”), the visuals always do a better job of conveying the theme and tone than anything from the plot or the script. Even the much-maligned ending is only a letdown from the point of view of having anything emotionally invested in the script; from a strictly visual standpoint, it’s quite lovely.

The Woman in the Window is worth seeing especially for Lang completists; it’s got ample visual rewards and fits in nicely into his progression as a filmmaker from the German Expressionist era to his strong American noir period. It’s also got moments of unexpected humor, and Duryea’s performance as a throwback hood from a ’30s gangster picture is a treat. But its clunky plot and script, its standoffish relationship to the dark connotations of its own ideas, and its stone-slow pacing make it a minor noir. It would be unfair to view it as nothing more than a dry run for Scarlet Street, but if only one of the two movies existed in Lang’s filmography, it’d be an easy choice. The Woman in the Window as a film too closely resembles the painting that kicks off its plot: it’s all surface, a gorgeous representation of something that ends up being quite a bit less than it appears. You can get a lot out of looking at it, but you probably don’t want to buy it and take it home.

Pingback: The Most Beautiful Fraud: The Woman in the Window « Screengrab In Exile