Akira Kurosawa’s films have become something of a sticky wicket for me. He’s obviously one of the greats of cinema, and at his best he’s nearly untouchable, but with some of his most lionized films, familiarity has bred, if not contempt, at least discomfort. The more I watch them, the more I notice little patterns and habits, which analysis — or over-analysis — turns into flaws. I’ve never really bought into the criticism, common in Japan, that he valorizes the elite; his focus on competent authority figures strikes me as more an obsession with professionalism, a la Howard Hawks, than it does any kind of statement on class or politics. But other factors are harder to ignore. His often glacial pace, with a few exceptions (particularly Ran) lack the weighty elegance of Yasujiro Ozu’s, and can come across less as someone attempting to set a contemplative mood and more someone in love with his own eye. Likewise, his determination to emphasize his humanist message can often lead to underscoring scenes with an awfully heavy hand.

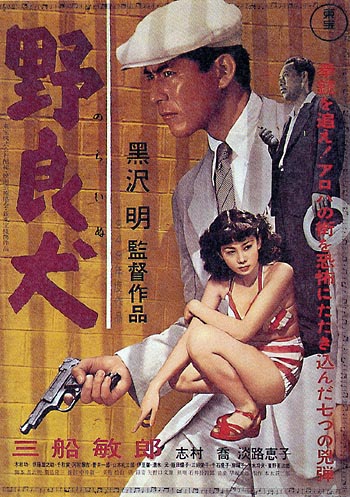

In an attempt to come to terms with these criticism, as well as to recapture what it is that I loved about the man in the first place, I recently decided to plunge into his early filmography, with which I was largely unfamiliar. The only pre-Rashomon film I can recall seeing is a barely-remembered college screening of The Judo Saga. So as a corrective, I decided to start with some of his ’40s material, and given my particular tastes, I thought Stray Dog would be a good place to start. Set just a few years after the war, it stars a young, hatchet-faced Toshiro Mifune as a rookie murder police whose Colt pistol is lifted off of him on the subway, sending him on a manic chase to recover it as it is used in an escalating series of crimes.

Stray Dog was one of several attempts by Kurosawa to work in the noir idiom — or, more precisely here, the police procedural. His self-identified model for the story was the work of Georges Simonon, and he also cited Jules Dassin’s The Naked City — a pure, straightforward cops-on-the-job number with fewer of Dassin’s usual bleak swaths of desperation and rudderless morality — but for me, it’s a film that plays more Italian than French. It works in a more neo-realist mode than in the deeply humanist, borderline didactic style than his later films, abetted greatly by some solid, naturalistic performances and most especially by Asakazu Nakai’s unromantic cinematography. Kurosawa, Nakai, and assistant director Ishiro Honda yank us headlong into a post-war Tokyo that is anything but the sprawling, gaudy, neon-lit metropolis of Seijun Suzuki; it’s a desolate, shabby, bombed-out wreck, with urban centers that look like desert villages, and busy streets that kick up dust under the director’s beloved weather-streaked skies.

This actually works strongly in the film’s favor; the lack of grandeur not only reduces the scope and prevents Kurosawa from getting carried away with historical conceits, but also allows him to narrow his focus onto the psychological tensions of the characters. He’s usually at his best when he maintains his idol Dostoyevsky’s observant perceptions of human behavior, while avoiding flat-footed attempts to recreate Dostoyevsky’s grand narratives of redemption. Here, the immediacy of the war and the tightened circumstances it inflicts on everyone are inescapable, not only in the landscape, but in the behavior of the primaries. Mifune’s police detective is impossibly rigid, rulebound, stiff and obedient; his station as a recent military veteran is impossible to miss, while his superior, played by Takashi Shimura, gets a load of his yes-sir-right-away-sir rap and immediately admonishes him: “Lighten up. This isn’t the army.” Shimura’s exasperated realist and Mifune’s nervy, gung-ho idealist form two points of a pyramid that terminates with Isao Kimura, playing another thorny, desperate veteran, scrambling just like like Mifune but on the opposite side of the law.

At least one stereotype about Kurosawa is cut to ribbons here: the knock that he can’t write interesting roles for women can’t survive a collision with the brassy, tough-talking showgirl played by Keiko Awaji. Scornful of the police, protective of her own circle, and barking her hardboiled dialogue with maximum slangy contempt, she’s the equal of any contemporary femme fatale in Western crime drama. She also hates to be dependent or obliged to anyone, and she’s ready to walk away at a moment’s notice. It’s a terrific character, and instantly one of the most fascinating women in Kurosawa’s filmography. Awaji, who’s still with us after appearing in a handful of Hollywood movies, has plenty of fun with it as well, decked out in scandalous outfits and throwing shade at Mifune every time he says something she perceives as patronizing or threatening.

For all its considerable strengths — and this will probably need repeat viewings, but for me, it surpasses The Bad Sleep Well and rivals High and Low among Kurosawa’s modern crime dramas — Stray Dog is far from perfect. It’s tight, but not particularly lean; there’s a lot of padding in the scenes where Mifune, in barely-needed drag as a homeless casualty of war, wanders through low-life Tokyo. (Another, where Mifune and Shimura pursue their prey to a baseball game, has so much goofy on-field footage that it seems like Kurosawa and his crew where just having a good time at the ballpark instead of working on a movie.) Some of its imagery is a bit too on-the-nose, as well. Kurosawa himself disliked the film; he seemed puzzled by its warm reception, and considered it a failed experiment.

Terrence Rafferty, the ex-New Yorker critic who penned the essay that appears in the Criterion edition of Stray Dog, thinks it’s a good thing that the movie failed in its attempt to emulate Simenon, as Kurosawa was (sniff) a maturing artist who was “outgrowing his influences”, and was “destined to become more than a reliable genre craftsman”. I agree with Rafferty’s assessment that Stray Dog may be Kurosawa’s first great film, but not at his dismissive waving away of its structure and composition; surely history has taught us that a miniature masterpiece can contain just as many profound insights into human nature, if not more, than big sprawling epics that are statements instead of films. Kurosawa’s reflection of Tokyo as a chaotic, sprawling reflection of the costs of war, and the slow disintegration of Mifune into a there-but-for-fortune-go-I perspective, are as powerful in Stray Dog‘s simple realism, if not more so, than any of the grand pronouncements of his later work. He may not have been destined to create films like this, but it’s nice to know that he could, and did.