One never expects an atomic bomb to go off in such a quiet way.

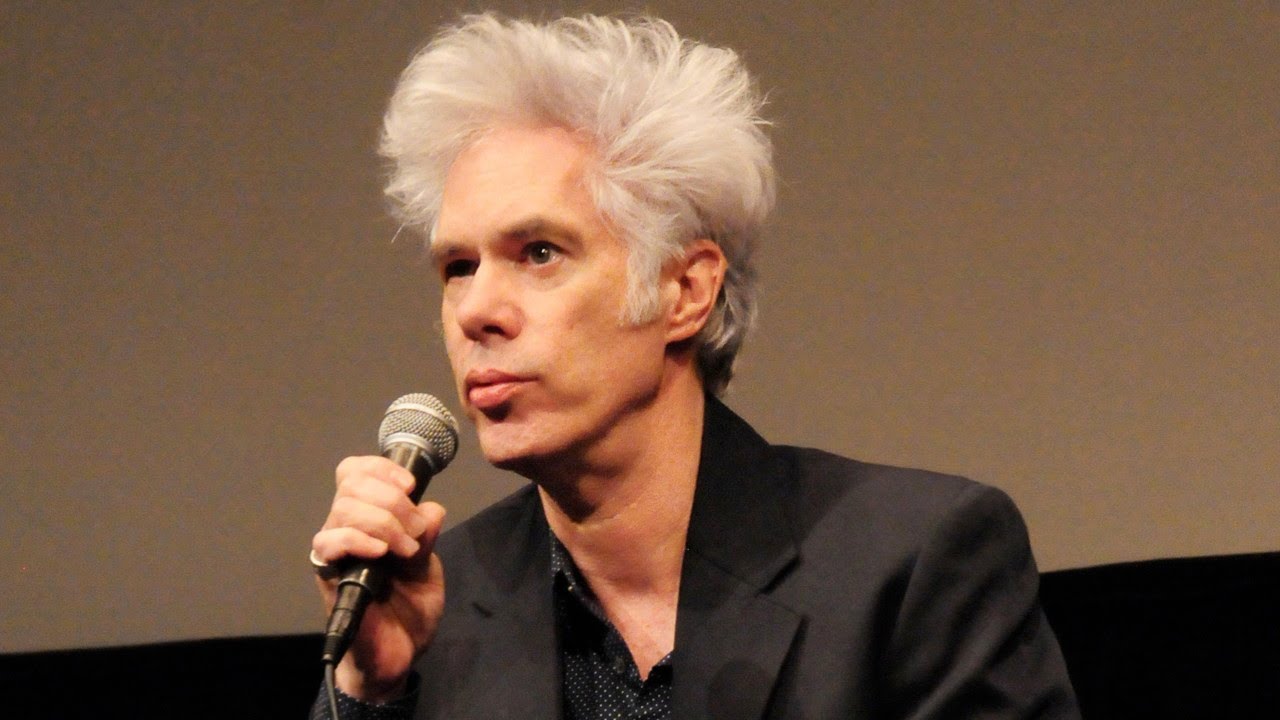

It’s also never supposed to be in the form of a long, lovely, exquisitely detailed shaggy dog joke. But Jim Jarmusch’s groundbreaking, entirely wonderful Stranger Than Paradise — which, astonishingly, is 31 years old this month — is exactly that: its form is that of a slow, hypnotic, frequently silent art film that would seem almost contemplative if it had any intellectual pretense; its function is that of an extended goof (on itself, on its characters, and on the audience); and its effect is that of a devastating explosion that clears away everything that existed in its space before and makes way for something new, albeit not without great cost. Much of what came after the film in terms of independent cinema followed its template, its pace, its concerns, and its methods; indie film became a cultural force in its wake, spawning its own clichés and shorthand, but none of that shorthand existed before Jarmusch introduced it.

Like all the best movies, Stranger Than Paradise is both of its time and timeless; it could not have been made except in the mid-1980s, but it also seems as though it could be made today, with only a few inconsequential elements seeming dated. It introduces us to lumpen slacker Willie (played by avant musician John Lurie, a lanky, surly, walking accent), who lives — barely — in a tiny apartment somewhere in New York that he pays for with the proceeds of various gambling endeavors, both legitimate and shady. He dresses in what, then and now, would be considered ‘vintage’ clothing, castoff leisure wear from decades ago that he turns from discounted junk into a cobbled-together style. He enjoys eating TV dinner, drinking cheap beer, and being left alone. His best friend, Eddie (character actor Richard Edson, up until then Sonic Youth’s drummer), resembles him in style, voice, and manner, but is a little shorter, a little more earnest, and a little dimmer. The only thing Willie keeps from Eddie is the fact that he moved to New York from Budapest; the two of them while away the hours doing nothing much.

Into this picture arrives his teenage cousin Eva (Eszter Balint, most recently the violin-playing foil of Louis C.K. on his own sitcom, a clear descendent of Stranger Than Paradise), who has come to America to go to school. Her relatives dump her on him, and, seeing in her an echo of himself, he instantly regrets her presence: she asks too many questions, wants too many things he can’t provide, and speaks in entirely the wrong kind of hipster argot for his tastes. But once she gets out on her own and shoplifts some TV dinners and cigarettes, she realizes that she’s down to clown in just his way — and he and Eddie begin a curious friendship with Eva that spaces out over a year, three different cities, and a whole lot of sitting around.

The cigarettes that Eva steals for Willie are Chesterfields — even in 1984 an archaic old-man brand. That’s the sort of detail Stranger Than Paradise gets exactly right every time, and makes every corner of its frame so compellingly watchable even when nothing is happening (which is most of the time, and by design). One could argue that Jarmusch had no choice but to get things right; he was working on an almost nonexistent budget and didn’t have the resources to waste on recreating anything but the beautiful, desolate reality of his locations. But that’s what good filmmakers, like good photographers, do: they force you to look at the banal, the shopworn, the kitschy and foolish things around you that you normally take for granted, and they use their precise focus to make you realize the defective perfection of the everyday.

As he would go on to do in all his best work, Jarmusch also wrings great performances out of deadpan expressions of boredom or annoyance; Willie’s laconic world-weariness, Eva’s subversive self-confidence, and especially Eddie’s well-meaning, simple naïvety convey much more emotion than they ever care to express. His script, too, wrests hilarity out of the dull and ordinary, as in a scene where Willie explains to a curious Eva the straightforward appeal of the TV dinner, or when his aunt matter-of-factly explains why she never loses at cards. And just as he manages to turn our eye to the stark appeal of the junky products and run-down locations — his New York isn’t the majestic, towering monument to civilization we see in Woody Allen movies, and his Florida isn’t the glittering playground of the uppers we get from television; both are temporary residences for the adrift proletariat, differing only in their weather — he brings tragic, hilarious characters into sharp focus by making us notice them: punk rock scenester Rockets Redglare as a loudmouthed, bullying loser at a friendly card game; hip-hop pioneer Rammellzee as a confused drug dealer; even Jarmusch’s cinematographer, Tom DiCillo, as a blank-faced, chummy airline agent.

Of course, many people, especially those resistant to Jarmusch’s trademark bemused slow pace — somewhere between the realist glare of the Eastern European new age artists and the locked-in-place, all-encompassing eye of the early Japanese humanists — will object that Stranger Than Paradise is boring. It cannot be denied that nothing much happens (even the eventful ending is deliberately subverted by the final shot), and there are long stretches of inactivity in the film, intentionally calling into account the long stretches of inactivity in the lives of the people it portrays. Although they travel thousands of miles over the course of the film, Willie, Eva, and Eddie don’t really go anywhere. Their Cleveland is a frozen wasteland, their New York a testament to treading water, their Florida just another place to lose money. The three of them progress in space and time, but never manage to move forward. But that’s part of the joke, and it’s a pretty good one: you can take the slacker out of the city, but you can’t take the city out of the slacker. The three of them may be going nowhere, but they’re going there together, and they’re going in style. It’s never been such a pleasure to see nothing happen.