Orson Welles’ Mr. Arkadin (also known as Confidential Report, Dossier Secret, and a handful of other names) is one of the most difficult to assess items in the great man’s filmography, which is one reason I’ve resisted seeing it for so long. While the general consensus seems to be that it’s a noble failure, a lesser crime drama scuttled by production difficulties and the kind of studio meddling that made the butchering of The Magnificent Ambersons look downright halal, some critics scorn it as an abysmal failure that shouldn’t have been made in the first place, while others — most notably Shinji Aoyama, director of Eureka and Desert Moon — cite it as one of Welles’ hidden treasures, a great work on the highest level regardless of its mutant pedigree.

It’s likely that more people know the muddled history of Mr. Arkadin than have actually seen the film, which partly accounts for its curious reputation. Made during Welles’ first overseas exile, it fell out of his hands when he missed a deadline and his biggest financial backer seized the print, making his own highly questionable edits. Welles never got control of the thing again, and went to his grave thinking that it was, even more than Ambersons, his greatest disappointment; but, after a nearly uncountable number of revisions, re-releases and restorations, a ‘definitive’ version was released under the Criterion umbrella, put together based on Welles’ own notes, existing footage, and close readings of the source material. This version, guided by the likes of Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Rosenbaum, was lovingly crafted by people very much in synch with Welles’ aesthetic, but it will still have to forever bear the asterisk, not only because Welles was long dead by the time it was assembled, but because Mr. Arkadin was never much of a unified vision to begin with.

For one thing, it was based on not one, but four different stories, and was originally meant to star Harry Lime, Welles’ character from The Third Man. Audiences really went for his roguish anti-hero persona, and Lime (despite the handicap of having died in the film) went on to become a popular fixture in pulp stories, radio shows, and other media; Mr. Arkadin was based on an amalgam of these — to be precise, three radio programs written by Welles and a novel by a hired ghostwriter. Some of the worst elements of the restored film betray these origins: its overcomplicated plot comes straight from the pulps, its muddled storyline shows the thumbprints of multiple narratives melted into a single storyline, and its dreadful amount of exposition, delivered in voiceover by the overburdened Robert Arden as the insufficiently hard-boiled Guy Van Stratten, comes straight out of old-time radio conventions. Welles was fresh off his early Shakespeare adaptations, which saw him engaging in some of the most gorgeous and undervalued direction of his career, but he was also desperate for a hit, and soaked in the kind of exotic crime drama that had not only served him well in the past (and would pay off handsomely, albeit with an equal amount of agonizing studio interference, in the future with Touch of Evil), so it’s understandable that he tried to make something of the morally shady radio plays that had paid his bills for a while in the States. But the sow’s ears of cheap, quick radio shows didn’t so easily turn out into the silk purses he had learned to love during his sojourn abroad.

At almost every turn, the commercial and the artistic instincts of Welles bash against one another. Of course, the restored version is still vastly handicapped by poor editing, missing footage, and the shortcuts that went into releasing a film that was not yet ready for release: sound synch is often terrible, stock footage sticks out like a sore thumb, makeup and costume are inconsistent and show off a need for post-production work that was never done, and the overall mess of a plot could have been hammered into a much tighter construction if it had been left in the hands of someone who cared more about it. But even beyond that, Mr. Arkadin is a hugely transitional film; even if Welles had kept control of it at every stage, it might have been as masterful as Touch of Evil, but it wouldn’t have been as coherent. Its director was too torn between the high and the low to give them the marriage he clearly wanted. (You can see why Rosenbaum and Bogdanovich, two men who have fought the same battle in their own work time and time again, would be so drawn to the prospect of reviving this film from obscurity.)

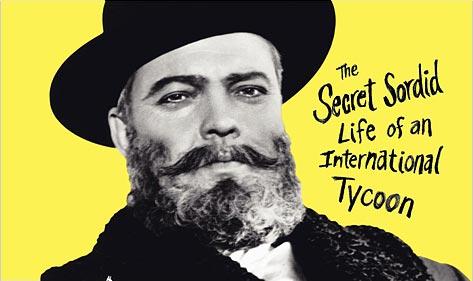

Although the plot — framed oddly in time, manically paced, and careening from one European capital to the next as quickly as one twist leads to another — falls apart under the least scrutiny, there is ample evidence that it should have been a much greater film than it is. From the stark opening shot of a dead body on the beach (immediately subverted, both intentionally by a totally bogus piece of narration by Welles that’s as genuine as the Coen Brothers’ assurance that Fargo was based on a true story and unintentionally by some rickety stock footage of a private plane in flight) to the magnetic end credits played out over Paul Misraki’s magnificent score, Van Stratten’s search for the truth about enigmatic billionaire Gregory Arkadin flashes with potential that never quite pays off. But waiting for it to do so is one of the greatest pleasures I’ve had watching a movie in ages; if nothing else, Arkadin is proof of the adage that it’s more enjoyable to watch a great artist fuck up than it is to see a mediocre one succeed.

Welles was clearly in love with Europe, and it may be that he selected the overstuffed number of stories to serve as the basis of his strip just because it gave him the chance to shoot against the backdrop of so many beautiful locations. The set pieces and scenery in Mr. Arkadin are alone enough to justify watching it, and certain scenes — a mournful brass band playing a woozy version of “Silent Night”, a static shot of old artillery and new construction equipment (old Europe and new) covered in snow, a parade of penitents that looks disturbingly like a Klan rally — will stay with the viewer for ages. Cinematographer Jean Bourgoin does a terrific job, and in those moments where the lovely film work isn’t subverted by the awkward storytelling — in other words, when it’s clear that Welles himself had a hand in the editing — Mr. Arkadin does a worthy job of showing a huge story filled with astonishing spectacle played out against a very small scale. (He uses the very effective trick, more than once, of pulling back the camera into darkness so that all the action is framed into a tiny illuminated corner of the frame, until it again bursts out into some grand backdrop.)

Although his films usually feature unimpeachable acting, his stint in Europe — and, I would guess, his time working with Carol Reed — taught him a thing or two about casting as well. Mr. Arkadin is populated with the most amazing collection of lowlifes, frauds, hustlers, scrounging criminals, freaks, and dead-faced hoboes you’ll see outside of the German New Wave of the 1970s; his incredible cast (including compelling turns by Katina Paxinou, Suzanne Flon, Mischa Auer, Akim Tamiroff, and even Michael Redgrave) looks like nothing so much as the grotesqueries and cast-offs of Fassbinder or mid-period Herzog. Their ability to convey drunkenness, addiction, vertigo and all-around disorientation, both personally and in the greater world, is one of the recurring themes of the film, and you can also see plentiful evidence of what would develop into Welles’ later obsessions with identity, fraud, and fakery.

Too incoherent and jumbled to make a solid and unified whole, but far too impressive and full of wonderful moments to be written off as a patchwork, Mr. Arkadin is maybe, by its very inconsistency and inchoate nature, a perfect example of who Welles was as a filmmaker: overflowing with great ideas and no way to contain them, single-mindedly focused on brilliance but forever hobbled by the commercial demands of his occupation, and able to take odds and sods of recycled familiarity and fuse them with something stunningly new. It clearly isn’t a great film, but it’s just as clearly a film by a great filmmaker.