It is often said of films — documentaries in particular — that they are either timeless and universal, or that they capture a very specific time and place. Chris Marker’s first feature film, Le Joli Mai (co-directed with cameraman Pierre Lhomme), manages the neat trick of being both of those things.

Le Joli Mai was assembled out of vast amounts of footage taken by Marker and Lhomme in May of 1962, while the former was putting together the film that would become La Jette. There is, structurally, very little to it: an ongoing succession of street interviews with Parisians, representing every section of humanity in that teeming, beautiful city. There are men, women, children, teens, the elderly, white Frenchmen, black Beninese, Arabs from Algeria, and people from every walk of life, from soldiers to stockbrokers to unemployed housekeepers. The interviewers (Marker and a handful of handpicked assistants) attempt to guide their conversations to a certain degree, but they are easily distracted, and more or less let their subjects talk about whatever they like. Narration and music makes it something of a tone poem, but this does not force any kind of cohesion. Themes suggest themselves obliquely and in passing, refusing clarity until the very end.

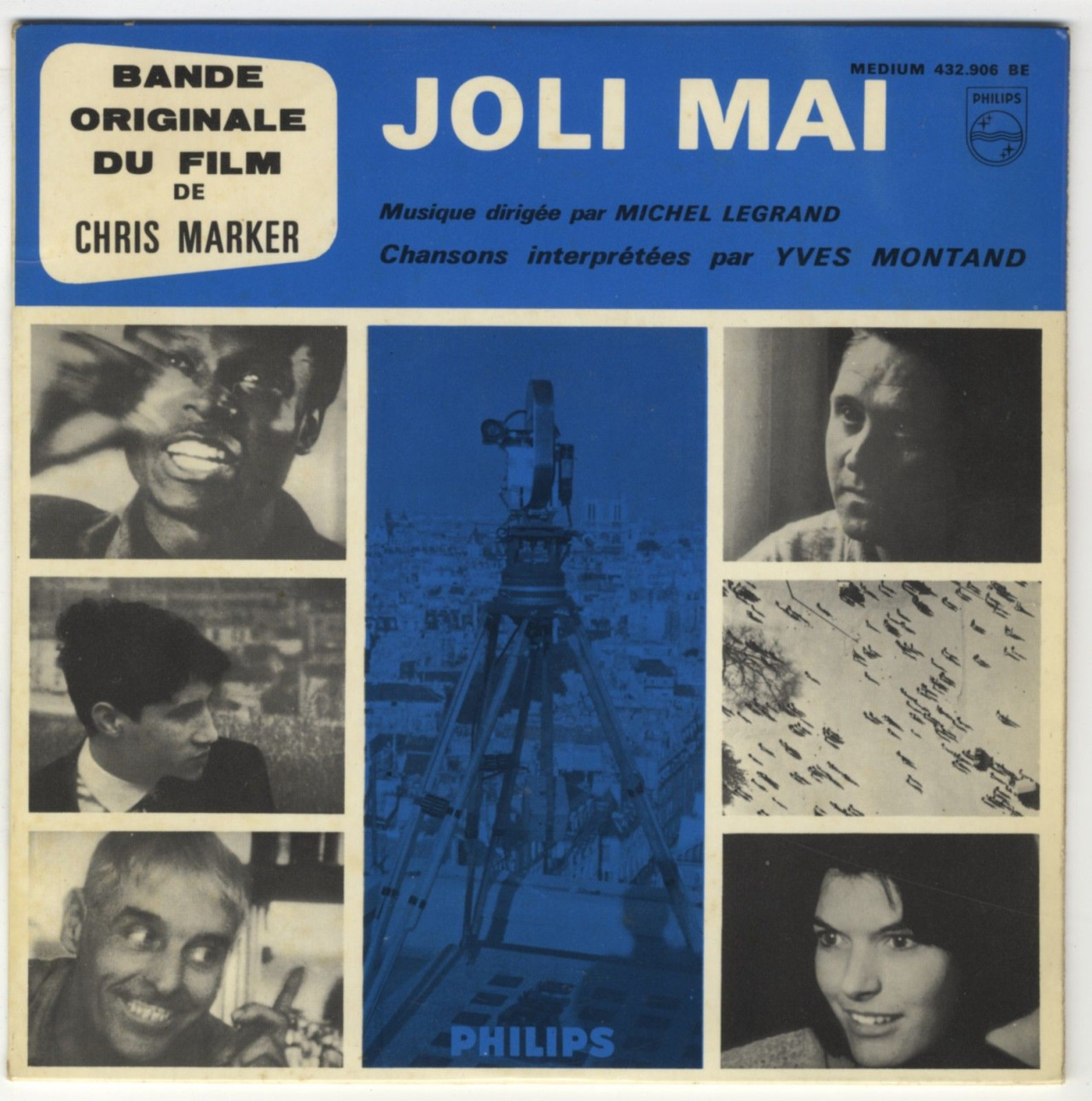

The narration and music is provided by Michel Legrand, Simone Signoret, and Yves Montand, making it the most French thing imaginable. Its setting is unwaveringly and irresistibly Paris, and Paris at a very particular time: May of 1962 marked the convergence of a number of events that would shake up France’s entire self-image, and determine for decades to come the directions it would take. War with French Indochina was over (and war with its successor, Vietnam, was just about to become America’s problem); war in Algeria was likewise coming to a close, and neither ended with much glory to be had for la belle France. Labor strikes and a restless left were putting pressure on the DeGaulle government, as was an embittered and embarrassed right; infuriated by the loss of Algeria, a group of generals at first attempted a coup and then formed a terrorist organization. A housing crisis had arisen as immigrants moved into the city and longtime residents sought relief from slums battered by decay and wartime damage. All of these factors and more converged to make a beautiful springtime in Paris into a nervous and uncertain period for those citizens willing to discuss them; Le Joli Mai is as specific a product of its time as can be imagined.

And yet, for all that, it has lost almost nothing of its relevance; seeing it today, it is striking how much of it could be tied directly not only to our own time, but to our places here in America. Men discuss money as if it is the only important thing; women talk about their changing roles and expectations; Arab men talk about the devastation war brought to their families; blacks discuss their encounters with racism; the well-off rail against troublemaking radicals, while the poor wonder how they’re ever going to make it. Everyone talks to Marker’s camera with an agenda they brought themselves, and he lets them craft the shape of the discussion, even as his interviewers guide it in subtle ways. The only thing that makes it seem out of time is the black and white camerawork and the fact that we see working-class people on screen.

The camera eye is stunning — in between fixed interviews, it captures some astonishing shots of the city at rest and in motion — but what’s so fascinating about it is its playfulness and ease. It seems to be easily distracted — by a lounging cat, a spider crawling down the lapel of a man’s suit, a cartoonish-looking retired sailor in the background. The interview process, too, seems at times arbitrary and even a bit flighty; it follows the fire, not the smoke. At one point, a pair of callow boys employed as gofers at the stock exchange fumble around with their half-formed conceptions of the future they see for themselves, when, at a critical moment, a loud-mouthed stockbroker hollers at Marker’s crew to stop harassing them. Seconds later, it is the stockbroker who is in the center of the frame, clumsily answering the same questions himself.

It is especially compelling to watch Le Joli Mai with the context of Marker’s later career and politics. His leftist politics are hardly hidden away here, but even when they are overt, they are never didactic; he lets his subjects descry their own visions of happiness and meaning, and he steers them towards discussing politics even as they vehemently deny they intend to do any such thing. But the currents at work in the film — the re-entrenchment of DeGaulle’s power; the shift in the political landscape due to the arrival of ethnic minorities, the enfranchisement of women, and the empowerment of student and worker groups; the trial of the generals and its fallout, as well as the shaken confidence of the nation as the French imperial phase ground to an ignominious halt — all would culminate in the most critical May in Paris’ history in 1968. But as electrifying as those events were, and as sympathetic to them as Marker must have been (there are echoes of the Lettrist and Situationist critique running through nearly everything about Le Joli Mai), we are also privileged to know his future, and how, only nine years later, he would document in A Grin without a Cat the failure of the left to realize its promise of global transformation, and the way it curdled into something smaller and less tangible.

Being a Chris Marker film, it is naturally broken up with unforgettable moments of visual sharpness (a woman walks alone across the high railings of a museum; an old man gnaws gloomily on a cigar; a young bride seems cross and alone at her own wedding; a dance party careens out of control like a car wreck) and emotional power (a mother of six swoons over the spacious new apartment her family is being moved to; a radical taunts the camera crew, mistaking them for government pawns; a man challenges his friend to answer a question honestly; a pair of architects dreamily chat about their ideal residential designs). Even this early on, Marker was truly making something much more rich and strange than mere documentaries, and the restoration of Le Joli Mai presents us with something uniquely of a moment and completely freed from circumstance. It is a film of the eternal human city.