“The darkest place is under the candlestick.” — ‘Me’

Devils on the Doorstep manages to pull off, with near-total success, something so frustratingly difficult to do in film, no one has really managed to accomplish it since Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove: make a work of art that fully captures the insanity and horror of war, while simultaneously being an achingly funny black comedy.

Set in the waning days of the Second World War, the film takes place in a tiny village at the end of the Great Wall by the name of Rack Armor Terrace — a seemingly nonsensical name that, as will many other elements of Devils on the Doorstep, transform in character, meaning and importance later on. The Japanese have occupied China for over seven years, and, in an object lesson about how even the worst traumas can accrue comfort through the familiarity of routine, things have settled into a simple rut for both sides. Every day, a Japanese commander leads his clattering marching band on a trek around the village, waves unacknowledged greetings to a gunboat forever patrolling the harbor, and hands out candy to the local kids and threats to the town toady, Er Bozi. Life continues more or less as usual under the thumb of the Imperial Army; no one is pleased to see symbols of Japanese nationalist furor pasted to the Great Wall, but farmers still farm, fishermen still fish, and a level-headed peasant, Dasan Ma(played by the film’s director, Wen Jiang) still carries on a slightly scandalous affair with his sister-in-law.

The reality of war sets in, as it so often does, when a shadowy resistance fighter (identifying himself only as “me”, which provides a running gag as Ma develops an absolute phobia about the word) dumps two captured Japanese in the peasant’s hut and vanishes into the night, vaguely encouraging their interrogation and promising dire consequences if they’re harmed. “What were you doing up so late?”, barks the invisible interrogator, pressing the barrel of a broom-handle automatic in Ma’s face; the truth is, he was fucking his brother’s wife, but he settles for the safer answer: “Thinking.” The pistol-wielding enigma responds: “Think away!” Thinking, unfortunately, isn’t Ma’s strong suit, and he immediately squeals to a collection of his fellow villagers — including some timid youngsters, the sniveling Er Bozi, elder statesman “Old Uncle” (who’s forever blabbing meaningless proverbs), and his lover’s crippled, crazy old father.

Ma is paralyzed with fear, since the nameless rebel has made it quite clear that he’ll be held responsible if anything happens to the captives, but the other villagers are just as terrified and just as afraid of being blamed — a message that’s critical to Jiang’s message that in times of crisis, inaction, fear and the desire not to be accountable can cripple even the best intentions. The captives, meanwhile, each resist in their own ways: the Japanese sergeant Kosaburo Hanaya is a fierce killer, filled with patriotic fervor, who screams dire threats at his captors in hopes of receiving an honorable death, while his translator, a Chinese collaborator named Hanchen Dong, is a conniving self-preservationist who tries, with some success, to convince the village elders that Hanaya’s enraged screaming is actually cooperative pleading. In one of the film’s funniest moments, Hanaya, hoping to provoke his keepers into killing him (he’s spent several hours dutifully bashing his own head into a post), instructs Dong to teach him certain phrases, as he’s heard that the Chinese will not tolerate any slandering of their ancestors. Instead, Dong feeds him a handful of stock travel-brochure banalities; when the villagers return, Hanaya twists his face into cartoonish spite while screaming at the top of his lungs “I AM YOUR SON! YOU ARE MY SISTER-IN-LAW! HAPPY NEW YEAR!”

Devils at the Doorstep is one of the more sophisticated comedies I’ve seen in recent years in this treatment of language; much of the comedy — and later, the drama — stems from the ambiguity of the spoken word, not only in the translation of Chinese to Japanese and back, but in various characters’ misunderstanding of threats, orders, and attitudes. Dong excuses Hanaya’s inexplicable behavior to Ma by claiming the Japanese sound the same whether they’re happy or angry; “Why do you think we call them devils?” In a later scene, two Japanese soldiers echo this dialogue as one explains to another that they must act like devils in order to get what they want from the simple-minded Chinese when, in fact, the locals are all to willing to go along to get along with their occupiers. Even the ‘interrogation’ of the Chinese prisoners is strangled by linguistic ambiguity: Old Uncle is determined to follow the letter of the law when it comes to questioning his prisoners, but since he knows nothing about warfare, strategy, tactics or the current military disposition of the Japanese forces, he repeatedly violates its spirit, dutifully transcribing Dong’s panicky translations of Hanaya’s impotent threats and filling up pages of text with vital information like “He’s afraid!” and “Please don’t kill us!”

Eventually, though, something must be done about the prisoners as the risk of holding onto them grows greater and the mysterious resistance fighters fail to return for him. Ma’s father-in-law scoots along on a wheeled platform, madly threatening to throttle them himself; but while his threats are hollow, at least he’s decisive. Everyone else, desperate to not put themselves at risk, vacillates endlessly, proposing impractical plans and offering to help only in the most helpless way possible. Keeping the prisoners alive is costing money, time, resources, and peace of mind, but the villagers continue to argue themselves into inertia. An attempt to have a legendary local swordsman execute the captives comes to naught, and eventually, the villagers simply decide to return them to the Japanese base. From there, the movie takes a dreadful turn into the horrible, as most forcefully seen when the occupied and occupiers come together for a big party. The villagers, who are determined to believe that the worst days are behind them, think it represents the end of the affair, but the Japanese commander knows better. It’s a masterful moment of audience manipulation, as everyone watching is aware that the whole thing will end in disaster but everyone on screen refuses to believe it.

Even at the very end, Devils on the Doorstep doesn’t let go of its pitch-black comic tone. The return of the prisoners to the Japanese HQ is marked by a inopportune donkey-fucking (of course, is there ever really a well-timed donkey-fucking?) that almost goes over the top in terms of comedy — it’s not quite the pie fight that wasn’t in Dr. Strangelove, but it comes close. In the denouement, when the government liberates the village, a pompous official named Major Gao spews out egotistical pontifications about heroism and patriotic duty while he carries out brutal reprisals against Chinese and Japanese alike, but he fails to hold the crowd’s attention; they laugh at runaway pigs, clumsy old men, and other absurdities while his two American handlers stand behind him, looking bored and chewing gum. Even the final scene is deflated of its seriousness by the untimely arrival of a fly, but while it still provides laughs, it’s saturated in tragedy and loss.

Jiang, who’s also well-known as an actor, questioned many of his own acting decisions throughout filming, especially as he was surrounded by more experienced screen veterans, but he made the right call: his performance isn’t the best in the movie, but it’s the one that holds everything together. He’s also got a terrific eye; for all its play with language, Devils is also a lovely movie to look at. He’s got a keen sense of details, from a donkey loaded down with fuel cans clanking down a dusty road to the haphazard path of a young child as he mindlessly recites a potentially deadly bit of information fed to him by Hanaya. His decision to stock the cast with a number of non-professionals, including crew members and locals, pays off, as the black & white camerawork transforms them into a convincingly realistic gaggle of curious and weathered faces. And his shot composition is reliably excellent; the area where the captured Japanese are kept is filmed, depending on the time and context, like a noir film streaked with shafts of light slashing through deep shadow, like a bit of European expressionism staffed with unseen darkened faces behind fluttering gauzy curtains, and like a slice of post-war realist cinema, with grimy faces shot just close enough to register their pain and confusion.

This is typical of the aforementioned sense of reversal that haunts the whole movie. While the transformations are rarely obvious, almost everyone and everything changes throughout the course of the film’s events, while the situation itself changes not at all. Ma begins as a simple man desperate to save his own skin; he ends as a man broken by his own knowledge and experience who seeks nothing but obliteration. Hayana starts out reviling the Chinese and screaming at them non-stop, while Dong plays the voice of conciliation, trying to seduce people into any action that will spare him; but as events progress, Hayana is humanized and repentant, while Dong lets his resentment of the Japanese curdle into raw, self-destructive hatred. Even Yu’er (played by Hongbo Jiang) undergoes a pleasant transformation: she begins with a largely thankless role as the timid lover of Ma, who exists only to be protected, but she gradually becomes a furious voice of reason, taking the men of the town to task for their paralytic inaction.

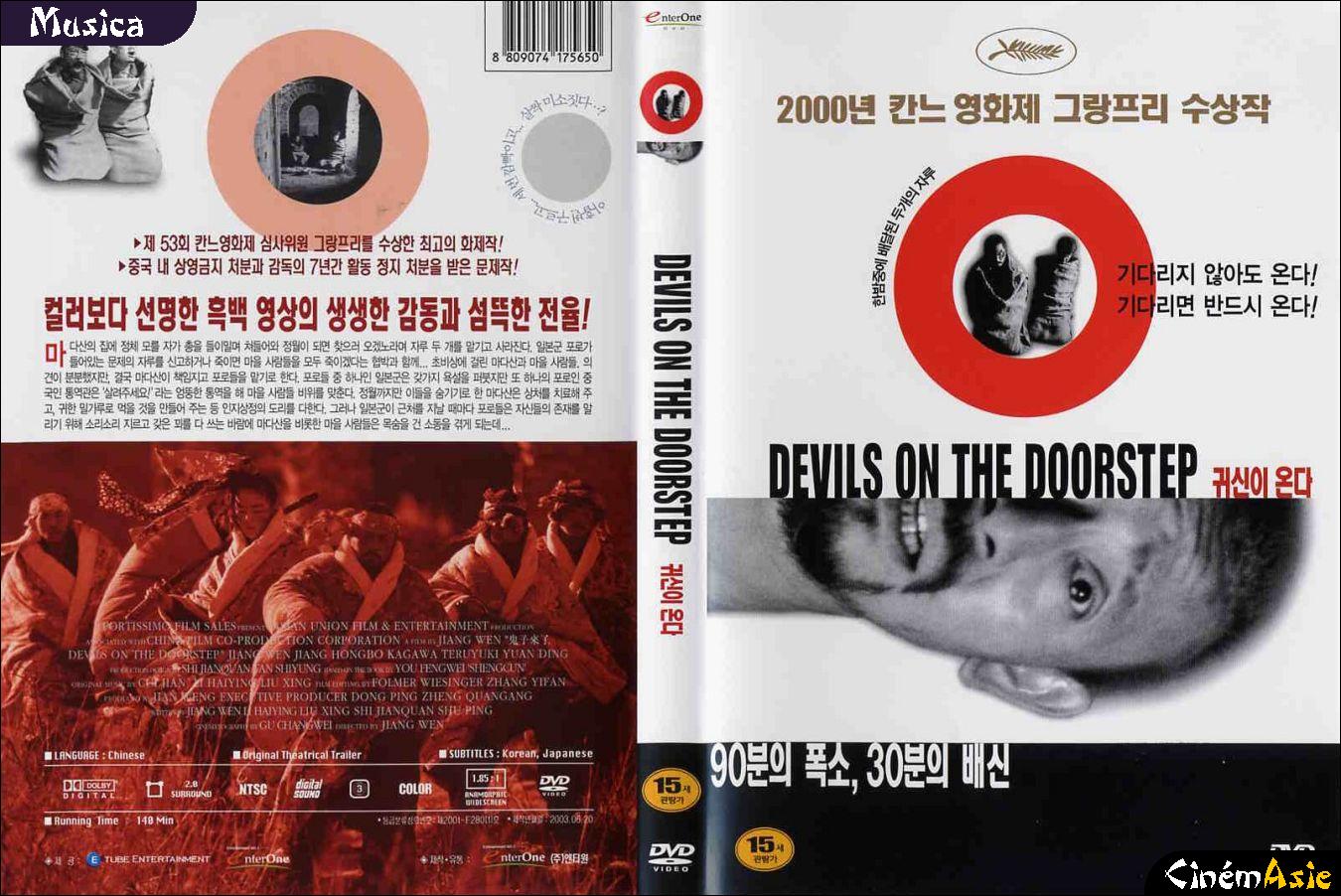

Ceaselessly funny, relentlessly black, extremely well-made and filled with valuable lessons about what a crisis can do to a community that fails to face up to it, Devils on the Doorstep had the bad luck to debut at Cannes in 2000, when it was up against Lars Von Trier’s celebrated Dancer in the Dark for the big prize. Jiang was granted the consolation of a Jury Grand Prize, but that was only the beginning of the film’s problems. As if to drive home the point about how international cooperation can be subverted by selfishness and self-regard, the film’s producers were unhappy with the final product; its Chinese backers were displeased with the cynical depiction of Chinese citizens during the war, while its Japanese backers disliked the portrayal of their soldiers as engaging in war crimes. Both threatened to pull their funding, which alone would have been enough to jeopardize the chance of the film receiving international distribution, but then, the real boom was lowered: the Chinese government was unhappy with Devils for political reasons, and was angry that Jiang brought it to Cannes without official approval. It was yanked out of international release, and Jiang wouldn’t direct another movie for seven years as punishment. But time and reputation won out, and now that the nationalistic blather of Major Gao has died down both in the film’s fiction and in real life, Devils on the Doorstep is easily seen by anyone who wants to see the razor-fine line of black comedy and wartime drama drawn like a samurai sword.