Suicide, as a tactic of war, seems to hold a particular horror for us. Because it is so seemingly foreign to the West (although, really, it bears little distinction from the kind of hopeless charges entirely common to the era of modern warfare), we tend to cite it as a fundamental difference between forces. The suicide bomber is a particularly egregious example of this, and leads some of our more hysterical observers to wonder how there can ever be peace with a people who seemingly do not value their own lives; in the Second World War, too, we seemed more able to understand the Germans, even though their hands controlled the horrendous machinery of genocide, than we did the Japanese, who threw themselves incautiously into the hail of certain death rather than be taken prisoner. As recently as 2007, Ken Burns’ documentary The War reflected this view that Japan produced a culture of unthinkable aliens, men who were not quite men devoted to an ideal of robotic suicide in the name of honor.

The truth is rather more muddled. It is no easy thing, even in the oppressive insanity of war, to convince men to engage in acts of mass suicide. No culture has ever cultivated a generation so devoid of the basic instincts of self-preservation that they will voluntarily snuff out their own lives en mass; and it will come as no surprise to those who have made a closer study of the dynamics of class and power that arguing a man into an act of self-destruction requires the constant pressure of an authoritarian culture. Regardless of the nobility and seeming hopelessness of their cause, suicide bombers are made, not born; it is not their blood, but deliberate and vicious calculation, selection and training — almost always by those who face no immediate risk themselves — that creates them. And, too, in the case of the kamikaze pilots and banzai soldiers, it was a relentless and brutal process of manipulation, propaganda, and systematic distortion and cruelty that made so many Japanese men go to their inevitable death long after their country’s position in the Second World War became untenable. And even then, it was no easy task to force these men to die. The enlisted men who bore the horrible brunt of this policy no more wanted to die then than you or I do today.

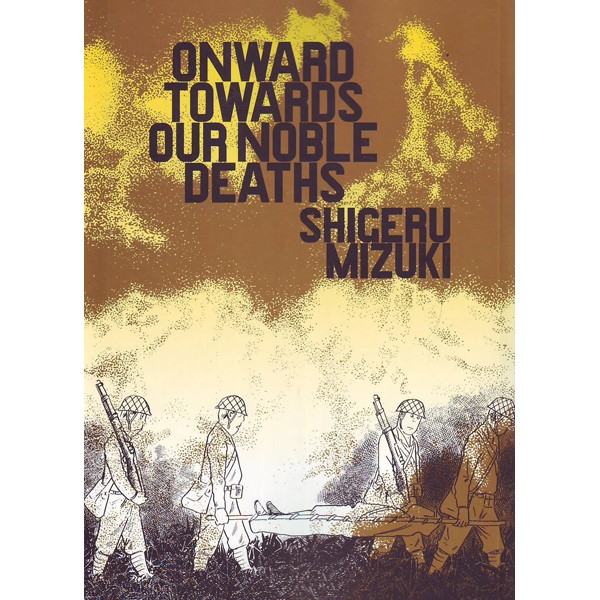

This is the most valuable lesson contained in the grim, beautiful, terrible book Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, written and drawn by Shigeru Mizuki in 1973. Mizuki is one of the most popular and beloved manga creators in Japan, but this is the first of his works to be given an English-language edition, in late 2011 by Drawn & Quarterly. (It’s a mystery why it took so long for such a towering figure’s work to appear in America, but it’s a useful reminder that we will never exhaust the culture the world has to offer us.) The story of a battalion of Japanese soldiers stationed on a remote island in what is now Papua New Guinea in the waning days of WWII, it is a book saturated with realism both horrific and banal, and Mizuki knows of what he speaks: he was stationed on that very island, and its story — of the gradual disintegration of his outfit and its eventual destruction via a senseless and ineffective suicide charge — is his own story. Though he survived the charge, he did so with the loss of one of his arms, and a case of malaria that almost killed him, depicted in the story with supreme irony: after his company receives the order to charge to their inevitable death, the soldier Maruyama (a stand-in for Mizuki himself), thirsty and deprived, drinks water from a brackish pool. Another soldier warns him that he’ll catch amoebic dysentery, to which he scornfully replies: “Who cares?”

The story follows Maruyama’s battalion from its surreally ordinary beginnings, as the men idle around a tropical island waiting to receive their marching orders, with nothing much to do but visit the single prostitute assigned to the entire company (a song she sings lamenting her cruel treatment and hopeless situation will later be sung by the men themselves as they prepare to die). Once they are sent to the island of New Britain, we are treated to the everyday frustrations and joys of the under-equipped grunt: a bit of extra pork one night, a chance to piss in the commander’s bath the next, and constant humiliation and abuse at the hands of the sergeant, a violent, unpredictable martinet. Even before the enemy arrives, death is everywhere: one soldier is crushed by a falling tree while helping build the army’s base; another dies overnight of dengue fever; a third falls off a boat and is chewed in half by alligators; a fourth, starving thanks to the meagre rations, chokes to death on a fish he’s caught. But when the Americans and British arrive — in a reversal of the typical Western war story, they are enigmatic, distant shapes, whose faces we almost never see — death becomes much more immediate, and infinitely more terrifying.

While Sgt. Honda — eventually killed by accident by one of his own men while patrolling the perimeter of the camp — is shown as an abusive, petty tyrant, it is the men at the top of the chain of command who are truly monstrous. We see immediately that none of the rank and file, from the grunts hobbling through the muck and constant rain to the field officers who have a first-hand appreciation of the costs of war — believe in the policy of gyokusai, or “honorable suicide”, where it is one’s duty to the country to become a “shattered jade”; it is, rather, a calculated policy by the generals and politicians to exert control over a military and populace who were beginning to see the warmongering of their leaders as the sham that it was. Everyone in the lower ranks questions the wisdom of the suicide charge; the enlisted men, who are well aware that their homeland is being bombed daily by Allied forces, wonder what the point of throwing their lives away can be when the entire empire is on the verge of collapse, and the front-line officers make the more strategic argument that expending hundreds of lives in a pointless charge is far less effective than staying alive and harrying the enemy for months or years with guerrilla warfare.

But the die has been cast; the decision has been made; the big lie cannot be rescinded so late in the game. The top men are shown to be cynically enforcing the idea of gyokusai for purely propagandistic reasons, while those in the middle — like the nervous and inexperienced Major Tadokoro, the battalion commander — are drunk on that same propaganda, insisting on expending the lives of their men like so much toilet paper in the name of emulating some long-ago legend of battle. And so it is that Maruyama and his men are chewed up and obliterated by the superior firepower of the Allies, and their commanders die a tawdry death on the nearby beach, tearfully gutting themselves before being shot in the back of the head by their seconds. The result is one of the most devastating condemnations of warfare and its myriad abuses against human dignity ever crafted. The whole notion of a “noble” suicide is portrayed as a sick joke played on the helpless by the powerful. In another gut-wrenching irony, the most decent character in the story — the humane medic Dr. Ishiyama — also commits suicide: after being abused and pilloried for protesting that the suicide charge is a grotesque waste of human potential, the gyokusai is a strategic disaster, and the Army is “the most diseased thing humanity has ever seen”, he takes his own life rather than be further beaten and insulted for his “stupid nonsense”.

It’s easy to see why Mizuki is such a highly praised cartoonist; he deploys visual imagery to a startling effect in Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, shaping patterns that only become clear as the story develops. It is not uncommon for manga artists to mix cartoonish figure drawing with photorealistic backgrounds, but I have seen few who use the technique with as much skill and effectiveness as Mizuki does here. His American soldiers are phantoms, shadowy harbingers of death; the only time we clearly see one’s face is immediately before he kills Maruyama, the sole survivor of the suicide charge. The Japanese are broadly drawn cartoons, with angular, caricatured faces and loping gaits, which makes it all the more devastating when they are ripped to pieces by the machines of war. His beautiful realism he saves for two things: the natural surroundings of the island jungles, still gorgeous to look at despite the idiotic intrusion of violent humanity; and the bodies of dead men, who, once robbed of life, can now no longer cause the world any harm, and thus become part of nature. It works perfectly, and in conjunction with his deft use of lettering to project sounds and environmental factors, only enhances the power of the story.

Almost seventy years later, having reached the age of 91, Mizuki is still fresh with rage over the callous wasting of his comrades’ lives, underscoring how unnatural the goykusai philsophy truly was. The massive casualties and complete lack of impact caused by the suicide charges never dissuaded the brass from using them; in fact, when the Battle of Peleliu was over, having cost the lives of over 10,000 Japanese troops, and with less than 20 surviving the constant banzai attacks, it was not condemned as a meaningless slaughter, but held up as the ideal for how all Japanese soldiers should be willing to die for the homeland. From that point forward, even as the war situation deteriorated, the military dictatorship pushed the propaganda that it was shameful to live in the aftermath of a losing battle; this madness, strongly opposed both at home and in the field, doubtless edged the U.S. closer to using the atomic bomb. “In our military,” Mizuki says in his afterword, “soldiers and socks were consumables. But when it came to death, it turns out we were humans after all…whenever I write a story about the war, I can’t help the blind rage that surges up in me.” That rage resulted in the creation of one of the most simple, straightforward and effective condemnation of the waste of human potential by war that’s ever been crafted.