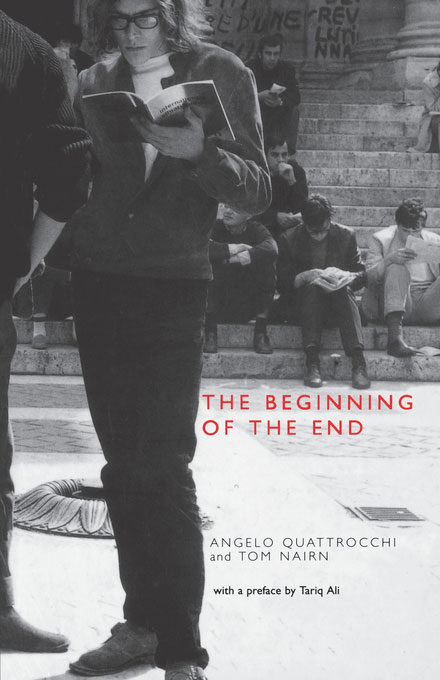

As noted when we talked about John Merriman’s Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune, my reading project for this year, where the only nonfiction I read will be about the Paris Commune of 1871 and the French revolts of May 1968, will begin at the end. Massacre, while an excellent history of the entire Commune, dwells specifically on its violent demise at the hands of Adolphe Thiers and his brutal Versaillais troops. My first book of the year on the events of May ’68, The Beginning of the End by Angelo Quattrocchi and Tom Nairn, is also a wider telling, but its focus is on the less violent but still tragic downfall of the student/labor uprising, this time because of the clever machinations of Charles DeGaulle and the inertia of the Parti Communiste Français. The former was an organized and intentional slaughter, while the latter was a failure of imagination and will; but both had devastating effects on the left and its ability to seize crucial political moments.

Although a slight volume, The Beginning of the End has a lot going for it. As Tariq Ali, ever a reliable chronicler of missed opportunities on the left, explains in his excellent introduction, Quattrocchi and Nairn are near-total opposites, but their accounts of the street battles of Paris that fateful summer are almost perfectly complementary. Quattrocchi was young, closer in age to the student rioters he was covering for Avanti!, the Italian socialist newspaper; his half of the book is enraged, poetic, and violently contemporary, befitting his anarchist politics and his background as a poet. Nairn, an older Scotsman closer in style and temperament to the workers whose simultaneous uprising formed the powerful but often uncomfortable alliance of May ’68, was teaching at the Hornsey College of Art in London when the shit went down and participated in its own notorious shutdown at the same time. His half of the book is regretful, academic, and rigorously historical, much better suited to an academic and Marxist framework. But both provide invaluable, crucially first-hand accounts of a miraculous moment in modern history, when a major Western power very nearly had a massive popular revolution without a shot being fired.

It is no secret that I view both the Paris Commune and the May ’68 revolt with something like religious awe. I have always believed that if we are to ever have a good and lasting revolution, it will come the way they came: not out of a void, not unplanned or un-prepared-for, but unexpected, spontaneous, unpredictable, and uncontrollable: the sudden sounding of a voice that had long forgotten itself, speaking on behalf of a whole people, and demanding not just a series of reformist acquiescences, but a total transformation of society from the ground up. I believe, with Rosa Luxemburg, that our victory will come not as a result of academic study or theoretical exercise, but as a result of our presence at a moment of sudden historical upheaval of which we must necessarily be a part — that “in the middle of history, in the middle of progress, in the middle of the fight we learn how we must fight…that the great masses of the working people first forge from their own consciousness, from their own belief, and even from their own understanding, the weapons of their own liberation.” But it is also no secret that I know how precious, how tenuous, and how maddeningly difficult this process can be, and how easily it can fall apart, and how the enemies of equality and liberation are forever waiting patiently for one mistake, any mistake, that they can exploit to tear what we have made to pieces.

It’s for this reason that I’m more invested in Quattrocchi’s manically beautiful half of the book than Nairn’s account, dry and bitter like vermouth. Nairn’s work is obviously the more intellectually accomplished and mature contribution, and he has moments of stunning clarity especially in his historical comparisons; his work on nationalism is not always convincing, but he does a fine job here of laying out exactly why things happened the way they did in France, and why they didn’t happen (and probably couldn’t have happened) anywhere else the same way, and what that all means for the future. The book wouldn’t exist without him, or at least it wouldn’t be nearly as compelling. But he is suffused with a pessimism that borders on cynicism, and his deep dives into the policies and conflicts between the warring left factions of the time can be a bit enervating. If his attitude towards the whole affair seems perpetually on the verge of defeatism, it’s understandable; he had just gotten canned from his teaching job because of his participation in the occupation of Hornsey. But in retrospect, it reads less like the work of a revolutionary and more like a man who was looking for an excuse to minimize the importance of what he’d seen.

Quattrocchi’s section, on the other hand, is pure juice, nothing but adrenaline and acceleration, all gas, no brakes. He alone seems radically aware that what is happening is both a political revolution and a social one (it failed as the former and succeeded as the latter). He was on the ground for the whole show, and while less than 300 miles separates Paris and London, his proximity makes all the difference. His telling of the story is immediate, exhausted, and full of spite: for the cops who so casually brutalize their own people, for the political figures who cadge around for petty advantages when total transformation is within reach, for DeGaulle, “the eternal shit, the canaille“. And, with urgency and clarity, from the middle of a beehive of activity, of people fighting desperately to protect what they have built overnight while engaging in the creation of an entirely new reality at the same time, he sees the cracks in the structure that will eventually break open and let DeGaulle and his cops and the political opportunists come pouring in.

Both men saw the rise and the fall of a stunning experiment in reshaping the world, from only a slight distance in geography and perspective. Both narrate its heartbreaking demise in an incredibly compelling way, full of important lessons to us; we are only fifty years removed, but we are also a long and eventful century away. The Beginning of the End may prove to be just what its title promises, but if we read its cautions and keep our eyes forever open for those rare and magnificent historical moments, it may be exactly the opposite.