The second entry in our month of films by eccentric Japanese filmmaker Seijun Suzuki (who, at 92 and beset by health problems, keeps on keeping on and has just recently lensed a documentary and appeared in a new television commercial, a profitable sideline for which he is arguably better known in his homeland than for his directorial efforts) is 1963’s Youth of the Beast.

While Branded to Kill is generally considered Suzuki’s lunatic masterwork, Tokyo Drifter the film that made his reputation in the West, and Pistol Opera his triumphant modern-day comeback, in many ways, I think of Youth of the Beast as his most typical film — Suzuki at his most Suzukian, if you will. While it’s certainly filled with energy, it lacks the pure kinetic velocity of Drifter, and while it’s nowhere near a traditional crime drama, it doesn’t have the sheer lunatic twists of Branded; but Suzuki shows a mastery of color, sound, and motion here, in addition to his choice of a tremendous cast and hurtling jolts of excitement, that characterize all the best of his earlier and later work. For that reason, it’s the one film that I associate with him the most — not the apogee of his particular blend of movement and visual flair, but perhaps its most successful realization.

Youth of the Beast (the title comes from the novel upon which it’s based, and I can’t make any sense of it) is another of Suzuki’s early yakuza pictures, and in most ways it’s a pretty standard police procedure wedded to a gangster narrative. While its plot takes a lot of twists and turns (and is, like most of his work, a bit hard to make sense of, with some developments that are as clear as mud), it isn’t an especially complicated story, and anyone familiar with the same sort of cops vs. rackets movies from the U.S. will find it easy enough to follow along. Jo Mizuno, played with rugged masculine fury by Suzuki’s great male muse Joe Shishido, is the new thug in town, a casually violent and supremely cocky enforcer who suddenly shows up in Tokyo and starts wreaking havoc for no particular reason; after crossing a flunky in the employ of the biggest mob in town, he attracts their attention and is soon working for them himself. But Mizuno is not all that he appears to be, and it quickly becomes clear that he’s running a dangerous double-cross, pitting the two biggest yakuza gangs in the city against one another in hopes of destroying them both.

Structurally, Youth of the Beast is a pretty typical gangster picture, very much in the grain of the movies Suzuki cranked out nineteen to the dozen when he was young and trying to make a name for himself at Nikkatsu. It’s also, to western eyes, the Suzuki film most indebted to noir, from its stark black and white opening sequence, with two grim-faced cops investigating the double suicide of one of their colleagues and his young lover, to the overarching narrative of a disgraced cop working an elaborate revenge scheme to bring down criminals who are outside the reach of the law. (One of the interesting asides here is the identity of the mastermind; without delving too deep into spoiler territory, the way it plays out reflects the perplexing gender qualities of film noir. Femmes fatale were often women placed in the classic archetypes of temptresses, sexpots, or the ambitious but helpless, but still managed to lend them some degree of power that women in most films of the era lacked by attributing to them the qualities of intelligence, sophistication, and a certain type of independent agency, albeit channeled towards evil. Similarly, here, Suzuki places his characters within a clearly defined framework of Japanese femininity of the time — essentially, the demure and proper wife or the out-of-control slut — while allowing them to push back against those identities in somewhat unexpected ways.)

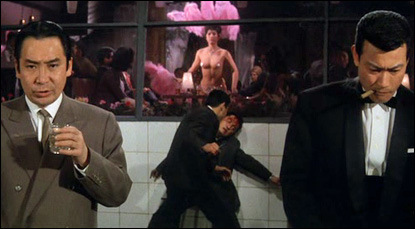

In every other sense, though, Youth of the Beast explodes all over the screen. Like all of Suzuki’s best work, it’s visually dynamite; even in the violent scenes (and it’s a very violent movie) where the blood and gore are obvious and clumsily done effects, they play so well against the backdrop of action-packed surrealism that they enhance rather than detract. It’s a movie full of fire, noise, blood, and smoke, barreling along like a moving car bomb; there’s never a dull moment, though Suzuki’s compositional brilliance does give us enough quiet moments to breathe, all the better to make the next outrageous stimulation all the more effective. His sound design, too — a major component of his films that too many critics overlook — is phenomenal here: in an early scene, the story shifts from black and white to color as Mizuno wreaks havoc in a yakuza nightclub. In the midst of the chaos, we abruptly switch to the offices of the yakuza boss, and for a moment, it seems as if there’s a technical error and the soundtrack has dropped out — only to have Suzuki reveal slowly, through movement, that we are now observing the same scene from behind soundproof glass. Youth of the Beast is filled with these moments of visual and sonic splendor, from the lovely design of a telephone to the clatter of wooden sandals along the sidewalks, and it never stops being a treat to take in.

There’s also a lot of fine acting here; Youth may be Suzuki’s best-cast film, and he crams it with instantly memorable character types. There’s the bloodless, peering mob boss who wears oversized spectacles, strokes a cat, and looks like a fey accountant; his lurching, alcoholic second-in-command; the big, dumb, gregarious enforcer who lives for guns and dames and takes an instant liking to Mizuno; the stern, no-nonsense cop who disapproves of Mizuno’s reckless vigilantism; and the rival mob boss, an aging fop with an inflated sense of self-importance and a bad toupée. There isn’t often a lot of depth or meaning in Suzuki’s movies, and this one is no exception, but he does toss us a few bones to chew on: the surprising inclusion of a gay character who isn’t played for cheap punchlines about his sexuality, and an interesting dichotomy between the successful new upstart yakuza gang, all tailor-made suits and Western habits, and the country manners of the old yakuza, with their traditional Japanese clothing and shabby offices.

Beginning with a highly formulaic story in a deeply predictable genre, Youth of the Beast takes sharp, pointed turns from its very beginning and hypnotizes you with its endless sensory gifts. It may not be the greatest Suzuki, but it’s the one I’d pick as exemplary of his greatest qualities as a director.