Even in the wicked world of chanson, where a borderline pedophile like Serge Gainsbourg or an accused Nazi collaborator like Maurice Chevalier can become a massive international superstar, Georges Brassens was an odd duck. Born in the beach town of Sète (which he remembered fondly in song his entire life), his teenage passions were the decadent poets and running with his street gang, with whom he engaged in everything from vandalism to jewel theft. When the Nazis conquered France, he was caught and forced to do wartime factory work. He escaped and hid out until the war’s end in a Parisian slum, surviving only through the kindness of others, who he later commemorated in “Chanson pour l’Auvergnat [Song for the Auvergne]”, which celebrates those who are charitable with no hope of reward. Falling into poetic decadence, he decided to stay there for the next two decades.

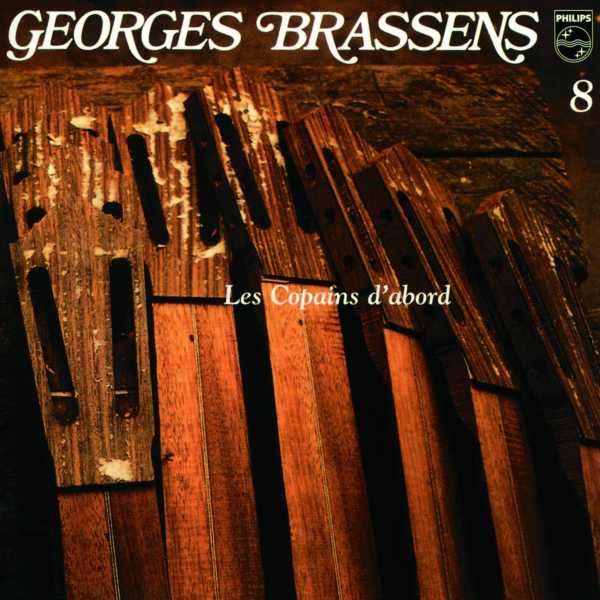

Brassens’ music is relatively straightforward; they’re usually simple pop compositions, hooky but uncomplicated, that he played on acoustic guitar. He had a wide range of influences; the title track of this 1964 compilation album, and one of his most popular songs, recalls post-war American country & western. Many have a proto-folk structure that anticipates Phil Ochs, and a few others are clearly derived from pre-war European jazz (there are even a few tracks, like the absurd “Élégie À un Rat de Cave [Elegy for a Cellar Rat]”, where he plays with a small jazz combo). But most stick to a fairly familiar and simple pattern that allows his true gifts as a lyricist to shine through. Brassens was a competent enough singer; not spectacular, but with a gift for little vocal tricks of over-enunciation and running lines together in a single breath, that made him particularly suited for chanson, where the important thing isn’t the tune, but the ability of the singer to show off the advantages of the French language. But most of all, he was a poet — not in the lazy way most decent pop music lyricists are described as poets, but in the true sense of a man who composes his work using carefully chosen, deliberately crafted images, structures and ideas. Some of his songs work better than others, but not one of them is lazy or slapped-together; he was a consummate craftsman who took full advantage of his language to turn audacious ideas into songs that dripped like honey in the ears.

But what truly set Georges Brassens apart from practitioners of modern chanson wasn’t his poetic precision; it was his choice of material. Brassens was a fiercely independent spirit his whole life, a true bohemian, a lifelong anti-authoritarian, and an outspoken anarchist sympathizer. His choice of subject matter had a definite turn to the bizarre, and he always found a way to go in unexpected directions with his songs. A simple love song would become shockingly erotic; an erotic song would become political; a political song would become downright subversive. “Chasse aux Papilons [Chase the Butterflies]”, for example, questions the traditional wisdom that love born of fiery, youthful passion cannot last; “Non-Demande en Mariage [Non-Proposal of Marriage]” finds a man begging his sweetheart not to get hitched so as to preserve their love for one another; and “Amoureux des Bancs Publics [Lovers on the Public Benches]” starts as a simple celebration of smooching in the park and turns into a condemnation of bluenoses and moralists who look down on such simple pleasures. “Mourir pour des Idees [To Die for Ideas]” seems like it will be a salute to those with the courage to lay down their lives for what they believe; instead, it becomes an attack on how the people who want you to die for an idea are never willing to do so themselves. And “Le Gorille [The Gorilla]” is a crazed piece of surreal political theater, where an escaped gorilla hunts down the judge in a death penalty case and, well, subjects him to some non-consensual gorilla lovin’. So notorious did Brassens become for his subject matter that he began commenting on it in his songs; “Le Pornographe [The Pornographer]” notes with some irony that when he was a boy, he was considered prudish and straight-edge, hating to hear people curse, only to grow up into someone known nationwide as one step removed from a smut peddler. Of course, he was being a bit disingenuous here, as anyone who can figure out the title of another song, “Cupidon s’en Fout”, will see.

I believe the songs of Brassens can be appreciated with no understanding of French, but this is with the caveat that all chansons emphasize the writing and singing of lyrics in a way that is inherently dependent on the French language. There are a couple of excellent sites providing English translations of his work, here and here; though they do terrific work, my main problem with them is that they translate in a fairly literal way, and make no attempt to present the translation as poetry, taking rhyme scheme and scansion into account, which leaves out an essential and intentional aspect of their composition. So, with the usual caveat that my French is extremely shaky (and feel free to suggest improvements), here’s my attempt at a more poetic translation of the title track of this anthology, a magnificent tribute to friendship.

Shipmates Come First/Les Copains d’Abord (Georges Brassons; original French lyrics and a different translation here)

No, this wasn’t the Raft of the Medusa, this craft of ours/Although deep in the ports that’s how it’s versed/It sailed easily on across the greatest of duck ponds/And it was called Shipmates Come First, Shipmates Come First.

Its fluctuat nec mergitur — well, it wasn’t really literature/And they hoped not to cross wizards and be cursed/But the mates and their master, they were not a bunch of bastards/But the freest friends in port, shipmates come first.

They weren’t friends interstellar like Castor and Pollux are/Or like Sodom and Gomorrah, even worse/They weren’t friends chosen by the Bureau, like Emerson and Thoreau/But they slapped each others’ backs — shipmates come first.

They surely were no angels, and they hadn’t read the Gospels/But all the rituals of friendship they’d rehearsed/John, Peter, Paul and company had as their only litany/Their doctrine and their creed: shipmates come first.

When disaster was discovered, that’s when friendship would take over/And it showed true north, and would not be reversed/And when they were in distress, they would send the SOS/but the semaphores all said “Shipmates come first”.

When the shipmates rendez-voused, it wasn’t often one refused/If someone didn’t show, they’d think him killed/But though he’d sink beneath the tide, they never forgot he died/After a hundred years or more, they missed him still.

I have boarded many ships, but only one survived the trip/And stayed on course wherever it traversed/It sailed easily on across the greatest of duck ponds/And it was called Shipmates Come First, Shipmates Come First.

Thanks for this great article, Leonard. I also like your translation of “les copains d’abord”. Have you tried recording a version? Ever since marrying into a French family who lives and breathes Brassens, I’ve been trying to translate his songs into singable English. Here’s my attempt at “les copains d’aboard”, called, “The Friend Ship”, which you can listen to here. I hope you enjoy it!