The notion of a non-fiction noir isn’t hard to understand — the resonance of noir fiction, after all, comes from how easily we recognize the patterns of spiraling violence, inescapable fate, and the darkness of the human soul from our real lives — but it’s rather difficult to find examples of. True crime books often shoot for a noir sensibility, but their tendency towards exploitation scuttles the attempt even on those rare occasions when the lackluster prose style doesn’t. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood is probably the best-known example of the genre; there are others, like James Ellroy’s memoir My Dark Places and even some collections of tabloid photography (I recommend Local News, a batch of vividly nasty shots from Los Angeles yellow papers curated by Diane Keaton, of all people). But the finest example of a noir tone in a non-fiction crime book I’ve ever read was written a good twenty years before anyone even thought up the idea of noir.

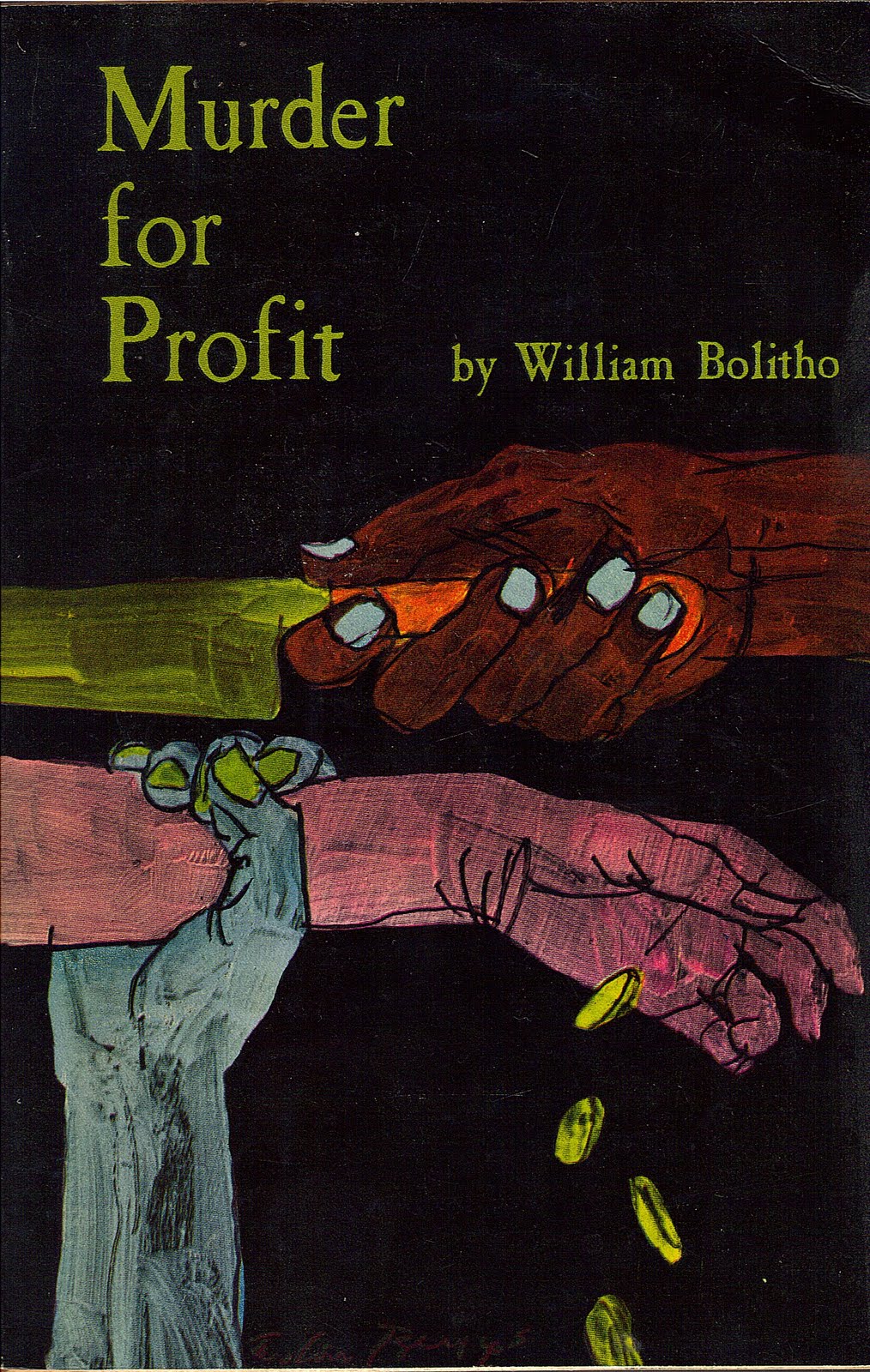

William Bolitho began writing his masterpiece, Murder for Profit, in the early 1920s, when he was still recovering from wounds suffered during World War I. Bolitho’s identity, fittingly enough, is a bit mysterious: consensus has it that he was British by way of South Africa, that he married under somewhat scandalous circumstances, and that he assumed the name of a famous banker and mine mogul to raise his social station (his real name is usually given as Charles or William Ryall). Whatever the case, he didn’t live long — his Great War injuries never quite left him — but he developed a reputation as a sharp-witted, intellectually curious and fearless writer, a self-made journalist who dabbled in the kind of speculative editorializing that would later characterize the New Journalists that emerged thirty years later. His other works included a revisionist take on Greek mythology, a first-person account of opium addiction, and a scathing look at the early days of Fascist Italy, but Murder for Profit, his sole dalliance with true crime, is his most lively and engaging.

While recuperating and confined to a hospital bed in France, he began reading about the “French Bluebeard”, Henri Désiré Landru, who had just been arrested and was due to stand trial. Landru would later be the subject of Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, but Bolitho became obsessed with him first, finding it fascinating how he took advantage of the lax law enforcement of wartime Paris to marry, rob, and murder widow after widow. The Landru case became a succès de scandale; “returned soldiers”, Bolitho noted, “followed with delighting recollection the accounts of Landru’s crimes — this host, back from killing, or suddenly relieved from the fear of being killed, with the taste of despair still under their tongues, learnt with a roar that a little funny man had all these years, behind their backs, been conducting a private war of his own, earnestly mimicking theirs, even to the casualties.”

Finding little interest from newspapers back home in the lurid trial and its inevitable culmination beneath the guillotine, Bolitho decided instead to delve into the history of mercenary homicide with an eye towards writing a sort of poetic history of killing for money. His most famous assassins were Burke and Hare, the notorious body-snatchers who found a gruesomely profitable way to supply the demand of medical schools for fresh cadavers; they would be written about dozens of times, including by Dylan Thomas in The Doctor and the Devils. He also looked into the case of Jean-Baptiste Troppmann, the Frenchman who murdered his entire family for the inheritance and who inspired a memorable essay by Ivan Turgenev, and George Joseph Smith, another merry-widow killer who drowned women in tin bathtubs just before the Great War. By the time he was almost finished with the book in 1926, another case — that of Fritz Haarmann, the Vampire of Hanover, who sold his victims as black-market meat — emerged and demanded inclusion.

The end result was Murder for Profit. It is a book both of and out of its time; it is suffused with psychological analysis and insight of a sort that was highly unusual for a history of crime written in the mid-1920s, when such approaches were still considered quackery by both law enforcement and the medical community. But it also falls prey to a great deal of racial nonsense, class snobbery, and a disdain for social theory that is all too typical of the period. Still, it has an unmistakable noir flavor: each chapter is a perfectly crafted short story, with a doomed criminal madman as the protagonist, a bleak psychological worldview suffused in intricate period detail and immaculate characterization, and a suffusion of shadows in which the entirety of the action takes place. But most of all, in the same way as the Black Mask boys were instantly recognizable by the hard-boiled patois of their cops and hoods, Murder for Profit is the ultimate in noir non-fiction because of its spectacularly gorgeous prose.

Though it’s a thousand miles removed from the tough-guy street prose of Chandler and Hammett, it’s unmistakably perfect, precisely the sort of thing that might have spawned the noir movement in some alternate reality where the genre drew on British interwar literature instead of postwar American film. Bolitho’s writing style is simply a thing of beauty, pitch-black and elegant while suffused with a wickedly complex insight even when it’s engaged in dime-store psychology. It’s rolling and dense without ever being too prolix, complicated and clever while still written for a popular audience, engagingly archaic but never dated. It’s just magnificent, and really without peer in the world of true crime — it even makes In Cold Blood seem hokey and stumbling at times. Out of print for generations, Murder for Profit is still available for a pittance from a variety of online sources and used book shops; the case I’ve made for it can’t progress any further than just presenting some of my favorite passages and letting you judge for yourself.

On William Burke’s occupation as a second-hand dealer:

“Men such as Burke wash towards the handling of half-worn-out goods as fatally as a cork to the shore, there to wait until another tide floats them over into the lonely reach where we find them. The modern economic system is a box with two bottoms. Where the smallest regular business of making and selling goods for consumption ends, begins the vast and incoherent traffic of half-used things.”

On the character of William Hare:

“If Burke was a dog, an ill-bred country mongrel that on sight any shepherd would shoot, Hare’s appearance had somewhat of the deviltry or the insane levity of the wolf.”

On what shapes the destiny of a murderer:

“In the mental life of most men there are no free thoughts, for each as it gets up is hooked by the foot in the piled accumulation of the past. Memory, with the background of punishments, fatigues, partings, regrets, breaks our actions as it hampers our thoughts, and its weight produces the prevalent mood that we call character. On a man like Burke this incubus of the past was especially heavy.”

On Burke’s planning of his crimes:

“Night and morning she would trundle and call, while her mate sat and hammered in a back room of the Log’s, in the artificial twilight, there occupied with the fascinating construction and furnishing of a cosmos, in the centre of which sat like a Buddha a crab-shaped little Irishman, hairy and muscular, meditating impassively on the mystery of lesser beings who whirled in a circle past him in his thoughts like dust in an orbit round the sun. Street, lodgers, city, state had sunk in his mind, filled with the obsession of his own needs and plans, to a phantom of the lightest irreality. While Nell went out with the barrow, the Burke universe was in evolution. It is no more wonder the heartless petty swindler is as happy in this ambiance as a bandit in a forest. Such germinating seed was William Burke in 1818, in the days before he met Hare. He was growing daily in the art of seeing men as material objects revolving round his central reality, as juicy shadows of another creation, to be cheated, used, fought, skinned, abolished when the only need he had come to recognise – the livelihood of William Burke and Helen M’Dougal – required. And these are the first lessons in murder.”

On Hare’s trial:

“His actions were sudden and unrelated to such a degree that he found it easy to raise a laugh; his thoughts had the inferior originality of a child. He was ticklish and sudden in his passions. In court Hare laughed whenever his throat tickled, whenever a fly blundered in a pane, even while he was charging himself with nightmares of infamy.”

On the origins of George Joseph Smith:

“We have but little to set against this claim of George Joseph Smith to be the issue of a phantasmagoria and not a human family. His father, the ‘cab driver’, according to this meagre document was also an insurance agent: an insecure category that may (risking something on the observed unspontaneity of a mass-murderer’s imagination) include the practice of flower and figure painting which, in one of his marriage explanations, George Joseph claimed for him. Beyond this cloudy genealogy, it is vain to seek. The very surname is clueless, for all family trees lose themselves among the Smiths. If ants have names for each other, they must use a tiny equivalent for Smith. It has no handle for the curious to meddle with. It is a name unlimited by space or time; it is an anonymity that may cover an earl or a gipsy evangelist, and a sort of evasion of the laws of heredity. ‘Smith’ suited the fantastic figure of this man who hated identification. With it his only heirloom, he could wander undetectable in the depths of any directory; he could enjoy some of the privilege of the disembodied spirit. He escapes the unplatonic ties of family, and promotes himself out of commonplace crime to the company of Mr. Hyde and Spring-Heeled Jack: a phantasm haunting the hinder terraces of the lower middle class, a subject for a new tale of wonder and imagination, where instead of hermits, are respectable spinsters; instead of dungeons, the shadows of boarding-house basements; instead of skulls, a more gruesome terror of tin baths.”

On how Smith psychologically prepared himself to murder his wife:

“To the making of this hypnosis in the few days that remain, he intensifies all his ways of thinking, as an athlete prepares his muscles for a record test. Everything that could recall to him reality, the personality of the woman beside him, he rigidly put out of mind. At all costs he must regard her as ‘raw material’, and crush out every reminder of her humanity. For fear she should put him under an obligation, he insists on doing all the housework himself, this lazy man. He does the shopping and insists on her staying in bed late, so that he can hate her. He had all the mean tidiness of routine of the incipient miser; he encouraged a hundred daily irritations of it, and he carefully concealed from her the way he liked things done, so that she could offend him. For the last few days he even paid the bills out of his own pocket, though every day he got nearer his last penny. The ways of a murderer and a boa constrictor are opposite. Where the one sweetens with his saliva, the other must carefully contrive to hate. Above all, he insisted with himself that it was business, business; and for this he forced himself to think only on the ledger-side of what he was doing. For this he haggled over the bath; if for the first time in his life he had bought a second-hand object without huckstering, it would have been to recognize that this was not business, but murder.”

On Smith’s selection of his next victim:

“So, as soon as she could help him to it, the bold spectre must have declared that he had a wild past. They parted late, she to notice the change in her room, as if all the furniture had been moved and ornamented, from the black hygienic bedstead to the row of pocket poets in limp leather. He, to exercises of deductive arithmetic, working from half-perceived rings and a brooch to the unknown resources of ladies that were ladies. Sleep sound, both of you: don’t worry that the other will not keep the rendezvous. Henceforth your lives, and your deaths, are welded together.”

On how Jean-Baptiste Troppmann’s childhood bullying shaped his murderous rage:

“He was always small for his age; his mother’s pampering had increased a congenital tendency towards indigestion. He was a yellow, spidery little boy. But his concentrated, prematurely determined nature came to the rescue. In his first fight, before the enemy had made up his mind, Jean-Baptiste was upon him and striking in the midst of the process of words and half-joking sparrings which usually precede such affairs amongst youngsters; with as much decision to hurt as a cornered rat, he overwhelmed him. Successes such as this gave him a fixed confidence in his power that made up for his weak muscles; and the exercises that it led him to undertake, especially jumping and running, let him correct them. Such was his belief in himself that no schoolboy feat of agility seemed out of his power, and each success increased his taste for astonishing the rest. His infirmity of stomach never left him; but he became a creature of leather and steel.”

On the chain of coincidence that led to Fritz Haarmann’s capture:

“A coincidence: one of those queer logical figures with which the stream of becoming sometimes playfully diversifies its course, one of life’s punning rhymes, which science hates and art abhors, but which fascinate the attention of mankind.”