Today’s Noirvember entry carries on a few themes from the last review of The Prowler: the presence of Evelyn Keyes (who I am assured ran a kicky newspaper column in the 1980s in Los Angeles full of takes on debauched Hollywood), the use of exotic locations (it’s the only classic-period noir I can think of that takes place in Hawaii, which makes me think that B. Clay Moore may have gotten a gander at it before he wrote the excellent Hawaiian Dick series), and protagonists with ridiculous names.

Hell’s Half Acre — currently available in a very nice restoration via Olive Films — was originally made in 1954 and released by B stalwarts Republic Pictures. Despite some misinformation floating around on the ever-reliable internet, it was an original story, and has no relationship to the hardboiled novel by Will Baer, the 2006 horror cheapie, or any of the various natural features across the U.S. with that name. It’s directed by John H. Auer, a third-tier noir stylist (and minor member of the Hapsburg Dynasty); he does a decent if unremarkable job, though he’s assisted by a solid camera job by John L. Russell and some clever editing by Fred Allen, who backed him up on his best film, City That Never Sleeps.

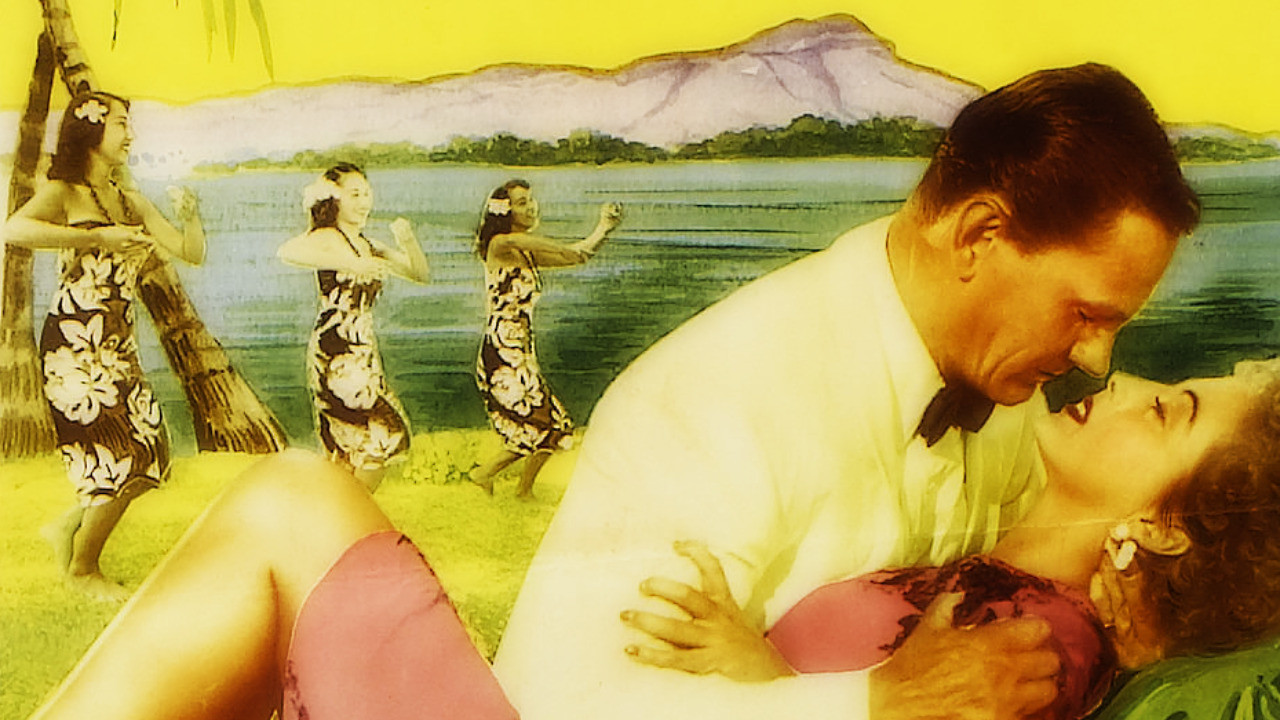

Scar-faced crooner Chet Chester — yes, that’s right, Chet Chester — seems to have it all. Played with fishy intensity by noir regular Wendell Corey, he runs his own tiki nightclub, the musical extravaganza he put together with his partner Roger Kong (Philip Ahn, one of many actors in the movie who made a living being professionally Asian in Golden Age Hollywood) is having its glorious debut, and he’s found a honey of a girlfriend in Hawaiian native Sally Lee (Nancy Gates). Unfortunately, he has a dark past as a syndicate boss, and as dark pasts always do in movies like this, it comes back to haunt him, and sooner rather than later. Knife-faced goon Slim Novak (Robert Costa), the third member of Chester and Kong’s racket, shows up intending to blackmail Chet by hipping the local cops to his dirty deeds. But Sally isn’t about to give up her cushy life so easily, and Slim looks downright shocked when she empties a revolver into his swank white dinner jacket.

Chet figures he’s got a decent chance of getting off with a slap on the wrist if he takes the fall and tells a jury that he killed a notorious hoodlum in self-defense, whereas Lee would surely get a harsh sentence for cold-bloodedly gunning down an unarmed man, blackmailer or no. But that’s when the plot takes a weird left turn: back home in the states, Donna Williams (Evelyn Keyes) is standing around listening to Chet’s groovy new record, and seems to recognize the voice; she rushes home to look at a photo of her late husband, Randy Williams (who’s only one “The Viper” away from being a mid-card N.W.A. draw in the late ’70s), only to find it inscribed with the exact same hokey line that closes out the song. Randy — a dead ringer for ol’ Chet Chester, naturally — was supposed to have been killed at Pearl Harbor, but Donna’s never quite accepted the loss, so she dumps her milktoast fiancé and flies off to Honolulu to get a straight answer.

Enlisting the aid of a spunky cab driver (delightfully played by a slumming Elsa Lanchester), she confabs with local police boss Chief Dan, in another fine performance from a surprisingly young-looking Keye Luke, who gives her a good-natured scolding when she busts out an all-Orientals-look-alike rap. Meanwhile, Roger Kong gets the idea that Chet’s about to make a break for America and, in an extremely creepy turn, leans hard on Sally, eventually depositing her in the morgue, where Chet makes a break for it to avenge her death. Figuring he’s hiding out in the slum district that gives the film its name, Donna poses as a taxi dancer, exposing herself to a variety of local sleazeballs (including local hustler Tubby Otis, played by Maytag repairman Jesse White). The ensuing scenes are a mad dash through Honolulu’s crummiest quarters, with everyone in town trying to find Chester for revenge, love, money, or the weight of the law. The situation really heats up when Donna gets dumped in a shithole apartment, menaced by the grim trio of Kong, Otis, and Otis’ wife, played by the luckless Marie Windsor. It all heads for an ending chick full of redemptive violence.

The whole thing gets kind of silly in terms of plot, but if you’re at all into post-war tiki culture, Hell’s Half Acre is an absolute delight: there’s some gorgeous location shots at the beginning, some great Asian character actors, and lots of beautiful island scenery, decor, and costume. The score (by someone named — come on, guys — R. Dale Butts) is stuffed with proto-exotica, and Chester’s “Polynesian Rhapsody” is a hoot to watch despite the absurd, stentorian narration from Corey. The entire movie is suffused with Orientalia, but it generally avoids cheap stereotypes and racist imagery, with the exception of the Chinese menu font used in the credits. Even Don the Beachcomber gets a “technical adviser” credit, meaning he probably got the producers loaded on mai tais between shoots.

As with a lot of minor noir films, the story can be sussed out quickly enough, and most of its pleasures lie in the cast and the atmosphere. The former involves the goofy admixture of noir regulars, Asian-American character actors, and a few old-Hollywood holdovers. Ahn is particularly menacing once his true nature becomes clear; one of the few yellowface stereotype turns comes by way of a skeevy informant named Ippy, played, strangely enough, by Leonard Strong, who made a career of playing various Asians despite being a lily-white Mormon from Salt Lake City); and there’s no other movie I can think of that features the Bride of Frankenstein whooping it up on the front of an outrigger canoe. As for the latter, the Hawaiian setting is responsible for most of the movie’s kick. Perhaps the best scene is a wordless montage of cops tearing the slum neighborhood apart; it’s a typical noir scene of uniforms tearing up back-room gambling parlors and busting up prostitution rackets, but it all takes place in Asian neighborhoods to the accompaniment of Hawaiian slack-key guitars! The mise-en-scène perfectly captures the early days of America’s post-war fascination with tiki culture, from the hula dancers at the airport to the swimsuit honeys lounging around in the musical numbers to the stock footage of surfers. It gives Hell’s Half Acre the sunniest of dispositions, making it perhaps the brightest noir ever made.