In defining the “perfect crime”, there is an interesting debate between criminologists. The most commonly held interpretation is that a so-called perfect crime is one where the perpetrator is never caught – where he gets away with the murder, robbery, or whatever other nefarious deed, and escapes justice entirely. A minority, but nonetheless influential position, however, says that for something to be a truly perfect crime, it must not even be known about. In other words, the perfect crime ceases to be perfect the minute someone even suspects it has been committed; it achieves perfection only insofar as its mere existence is a matter of speculation only.

It is this sort of crime to which Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, who would become the defendants in one of the 20th century’s most notorious trials, aspired to commit. Influenced by a whirlwind of dangerous factors – desperation, boredom, wealth, ego, sexual passion, and a profound misreading of the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche – the two men conspired to murder Loeb’s 14-year-old cousin Bobby Franks, luring him into a rented car and then splitting his skull with a chisel. Leopold in particular, drunk on his own sense of intellectual superiority, believed they would never be caught for the killing; it must have been terribly disappointing to his self-image when, only eight days later, he was hauled in by the police and incriminated on a flatulently obvious piece of evidence: he had left his glasses near where he dumped the body.

In such cases, one often has to wonder whether the criminal in question actually wants to be caught. The perfect crime, after all, is only of value to the perfect criminal – to a careful professional for whom it is of paramount value not to be caught, and whose crime has some tangible benefit. Leopold and Loeb were no criminals, perfect or otherwise; they were, rather, thrill-seeking sociopaths, bent on getting off on their own perceived superiority. They bore young Bobby Franks no especial ill will, and they certainly didn’t need the paltry amount of money they demanded from his family in a feint after his murder. They wanted to prove they could get away with murder. And what good is getting away with murder if, well, you get away with it?

That’s the premise of Rope, a play written only a few years removed from Leopold and Loeb’s infamous crime. It was written by Patrick Hamilton, who we’ve discussed here before; its combination of a tight structure, a compact frame, and a somewhat shocking approach made it his first big hit and guaranteed him an income even as his own life plunged further into darkness. He changed the setting from suburban Chicago to drawing-room London, and made his murders a bit closer in age to their victim; he also, out of necessity, downplayed the fact that the killers were romantically involved, though he didn’t entirely eradicate it. And while the necessity of the story’s transition into a whodunit required some shuffling about, Hamilton achieved it in a clever way: the story’s ‘detective’ (Rupert Cadell, a brilliant but dissipated poet who had been the killers’ teacher at school) was a curious amalgam of himself (an embittered alcoholic whose views on morality and respectability had been blackly tainted by personal horrors) and Clarence Darrow, the legendary defense attorney who defended Leopold and Loeb in real life. Like Darrow, he personally despised the boys and detested their crime (and the self-aggrandizing manner in which they justified it); but, like Darrow, his own unconventional morality led him to take some curious routes along the way, leaving the observer on uneasy footing about where exactly he stood.

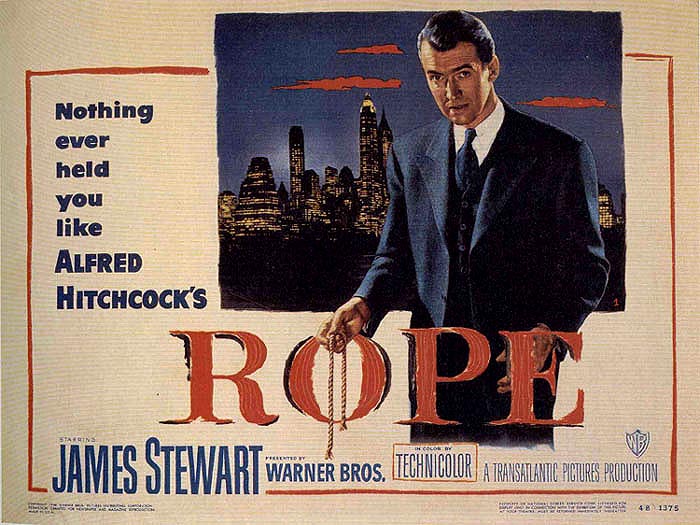

Rope, too, places the question of the “perfect crime” front and center in a disturbingly literal way. As it opens, the killers – the charismatic and smug Wyndham Brandon and his companion, the nervous and fragile Charles Granillo – have not only committed a murder, having strangled one of their classmates, but they intend to throw a party that same evening, inviting, among others, the victim’s father, who will drink and dine off of a large steamer trunk containing the corpse of his beloved son. Hamilton perfectly understands the element that separates the theoretical perfect crime from the practical one: that element is ego, and it is in no small supply in virtually every character on the stage. No one who didn’t, on some level, wish to be caught – wish to sacrifice his own life for the sake of telling the world what a clever bastard he’d been – would possibly take such an insane risk. And yet the tension of the story, of which there is a bountiful supply (as illustrated in its most famous adaptation, a 1948 film by Alfred Hitchcock), derives from the fact that Brandon and Granillo might just get away with it. It veers from the normal chamber whodunit because we know from the very beginning who’s responsible for the murder, and, inasmuch as we can ever know such a thing, why they did it; the only question is how much Cadell knows and when, and whether or not he’s going to do anything about it and why.

Hitchcock’s film is the way one usually encounters Rope in this country, where the play was never as huge a success as it was in its native England. This works for good and ill. Sacrificing his usual big-screen sense of openness, Hitchcock embraces the staged quality of the play, engaging in all sorts of visual trickery to make it pleasing to the eye; naturally, being the man he was, he also focuses more on the paranoia and dread of his killers than the forthrightness of his protagonist, though Jimmy Stewart is forever incapable of leaving his characters devoid of at least some degree of righteousness. Farley Granger preps for his fine work for Hitch playing a weak-willed smoothie in Strangers on a Train, stepping into the Granillo role, while Brandon is cleverly done by John Dall of Gun Crazy. But even with his wound-up editing and claustrophobic camera work, Hitchcock opens the story up a good bit (with script help from Hume Cronyn, of all people), and can’t help make a movie out of it.

A recent production of Rope I saw at the Ballard Underground, courtesy of director Justin Ison and Ghost Light Theatricals, conversely closed it all in, leaving the drawing-room qualities of the play (one of the last of the ‘well-made’ productions of the pre-modernist tradition) intact but ramping up the psychological tension, thus retaining the best qualities of the original while not throwing Hitchcock’s refinements entirely over the side. The arch dialogue is definitely a reminder of the days before postmodernism stripped away theatricality and honed language to a fine point, but it works given the scene and the setting, and while it’s not especially timely (murder has acquired a degree of brutality that makes a thrill-killing strangulation seem almost quaint, it’s a skillful production that keeps the power of the story intact, and reminds us of the genesis of one of the most enduring forms of noir storytelling: the perfect crime in the hands of imperfect criminals.