When you ask people what they think was the greatest baseball movie ever made, you usually get one of three answers: the charming, effusive Kevin Costner vehicle Bull Durham; the treacly, sentimental Kevin Costner vehicle Field of Dreams; or the moronic but enjoyable Major League, which at least has the advantage of not starring Kevin Costner. The witless adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s elegant The Natural also gets a lot of mentions, as does overblown and/or grody kiddie fare like The Sandlot and The Bad News Bears. (Just in terms of pure quality, Moneyball probably beats them all, but it’s sort of peripherally about baseball, and more about economics, statistics, and why we should all be thankful that we have Brad Pitt now instead of Kevin Costner.)

For me, though, the answer has always been Eight Men Out. This isn’t, as you might expect, because I’m a die-hard fan of the Chicago White Sox; if fandom had anything to do with it, I certainly wouldn’t want to celebrate a movie based on their most disgraceful moment, and possibly the darkest hour in all of professional sports. It’s because writer/director/star (!) John Sayles does a tremendous job of encapsulating everything amazing about baseball (its energy, its joy, its athleticism, its cultural influence, and its sheer beauty) along with everything terrible about it (the varied chicaneries and wrongdoings of the owners, the gamblers, the press, and even the fans), while never losing sight of the rollicking adventure-novel qualities of Eliot Asinof’s original book. Asinof was a minor-league ballplayer himself, and Sayles is a devoted fan, so they found sympathetic viewpoints and inspiration when the time came for the movie to be made.

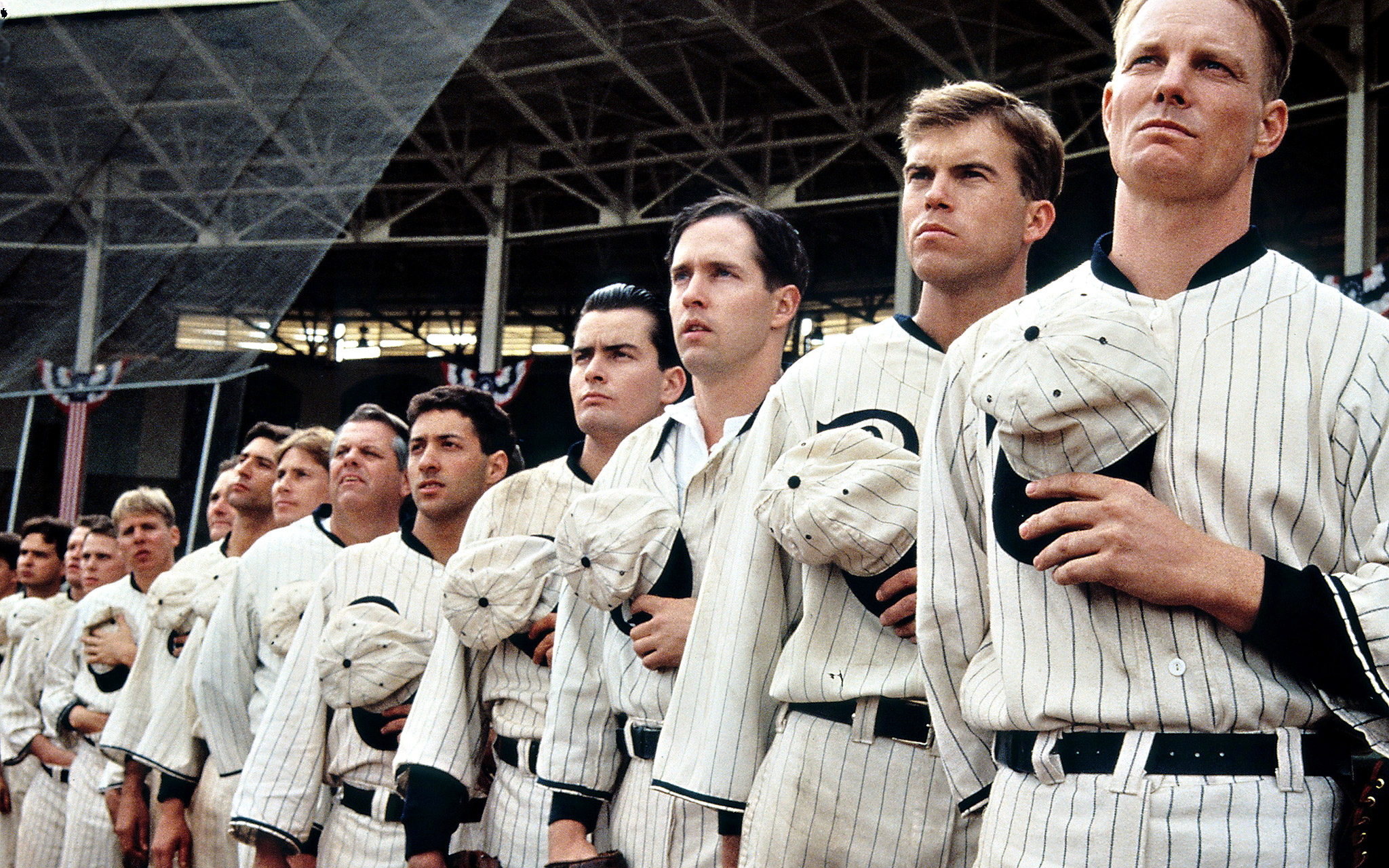

There’s an awful lot to love about Eight Men Out. Sayles assembled a dynamite cast to play the handful of men who conspired to fix the 1919 World Series; among the players, many of the best performances are by relatively unheralded actors. Gordon Clapp is stellar as the short-tempered catcher Ray Schalk, who isn’t in on the fix and is suitably furious when he learns his pitchers are blowing games on purpose; Jace Alexander is all grins and wonder as the sensational rookie Dickey Kerr, who likewise is joyfully innocent of what his teammates are up to. Bill Irwin is a real delight as the straight-laced star second baseman Eddie “Cocky” Collins, and John Mahoney is just terrific as Sox skipper Kid Gleason. David Strathairn is the movie’s emotional center as crooked spitballer Eddie Cicotte, nicely illustrating both the shame of the players who sold out the game and the damn good reasons they had for doing so, and as Chick Gandil, the big first baseman who cooked up the deal on the players’ end, Michael Rooker has a lot of heavy lifting to do and does it well. John Anderson is suitably grim and noxious as the sepulchral Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who the bosses bring in to restore public confidence in baseball; Charlie Sheen is an asshole, but he at least has the right role, playing asshole outfielder Hap Felsch. If there’s one stumbling block, it’s that D.B. Sweeney sells the dumb-hick angle a bit too hard as Shoeless Joe Jackson.

In the gambling community, Richard Edson (a ubiquitous character actor in the late ’80s, following a spell as, of all things, Sonic Youth’s drummer) is hilarious as thin-skinned pug Billy Maharg and Christopher Lloyd is typically fun as his partner, Sleepy Bill Burns, the ex-ballplayer who first came up with the idea for the fix. Kevin Tighe, an underrated character player, is toothy and oily as Boston wheeler-dealer Sport Sullivan, and Michael Lerner is brilliant as mastermind Arnold Rothstein, who holds Sullivan in dire contempt. The press box is a noteworthy weakness, cast-wise — Sayles himself plays Ring Lardner with an unflattering blend of fidelity and incompetence, and while it’s fun to see Studs Terkel as Hugh Fullerton, the newspaper jockey who broke the scandal, it’s still pretty much stunt casting. John Cusack is a tad oversincere — some might say corny — as Buck Weaver, though, and it’s his portrayal that’s one of the movie’s only historical problems.

In any story so specifically about a particular time and place, liberties have to be taken, so Sayles can be forgiven for compressing a lot of the story to fit it into the timeframe of a movie, and making its big issues comprehensible to viewers. Less understandable is why he soft-pedaled the role of some of the players in the scandal; Weaver indeed played his best, but he also went along with the scheme and didn’t tell anyone, which arguably makes him more culpable than the actual crooks. Joe Jackson’s role in the fix is to this day extremely murky, but he’s hardly the backwoods innocent portrayed in the film; in the book, it’s far more clear that he was indeed a bumpkin early on in his career, but that by the time the 1919 Series rolled around, he was a determined lover of the big-city vices of drinking, women, and gambling. The book is also superior in communicated just what a massive clusterfuck the fix really was, with at least three groups of gamblers, all thinking they were acting on their own interests, conspiring to make it happen and tripping up every step of the way, while Rothstein, the ultimate predator, sat back on got fat on them all while never once getting close enough to the action to put himself at risk.

Still, the movie does a great job of selling many of the most important parts of the story: how massively popular baseball was at the time, and how profoundly the ’19 World Series fix stunned a nation already reeling from the losses of the First World War; how badly Charlie Comiskey screwed the players who made him rich, and how clumsily he and the other owners conspired to simultaneously acquit the eight crooked ballplayers and make sure they never played again, thus making sure the owners came out smelling like a poor wounded rose; and, most tragically of all, the fact that the players — the only people necessary to play ball games — were the ones who got screwed the most, first by Comiskey, then by the gamblers and their own greed, and finally, by the baseball establishment, which at first swore it would protect them and then hung them out to dry rather than make the owners look culpable. That’s the good stuff, the heart of the real drama, and the reason that Eight Men Out is the best of all baseball movies: it reminds you of why you became a fan in the first place, while simultaneously recalling that the good guys don’t always win — and aren’t always the good guys.