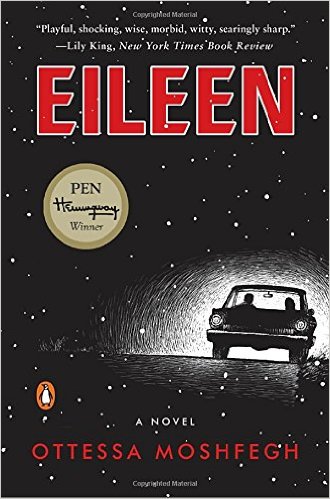

Ottessa Moshfegh is a hot property right now. Establishing herself as a writer of excellent stories in the early 2010s in the Paris Review and Granta, she has just published her first collection of short fiction, Homesick for Another World. It was her first novel, however, that really put her in the sights of the literary world: Eileen got her lots of critical attention and a degree of commercial success, culminating in a short-listing for the Man Booker prize in late 2016. Moshfegh’s touch with shorter forms is very special and shouldn’t be ignored, but it’s her first full-length work that truly engaged her and won her a national audience.

Eileen Dunlop, the titular character in this curious piece of work, is light-years removed from Moshfegh herself. She tells her own story as an elderly woman, confident and more than a bit cynical, looking back at a single transformative week from her early twenties; while Moshfegh is quick-witted, funny, urbane, and literate, Eileen is a shrinking violet who has curled enough to become twisted. Though we can never be sure that Eileen the narrator is being entirely straight with us about Eileen the person, the picture she paints is of a young woman still throttled by adolescent angst, addicted to sick pleasures and bizarre flights of fancy, coping passive-aggressively with her judgmental sister and alcoholic wreck of a father. Some critics have compared Eileen to a fictionalized Sylvia Plath, but she more often comes across as a gender-swapped Holden Caulfield: lacking Plath’s poetic soul or dark self-knowledge, Eileen is a ball of tension and subdued contempt.

Cataloguing Eileen’s strange behavior could take up the bulk of this review. Tenuously employed at a juvenile home for boys, she gives her work days over to perverse fantasies about one of the trustys, and spends her time at home alternately hiding from her father and tending to his helplessness. She keeps a dead mouse in her glove compartment; she eats and drinks garbage and forces herself to sick it all up, becoming obsessed with her own nausea and bowel movements. She is fascinated by bad odors and unpleasant bodily hygiene, both her own and those of others. Her thoughts are filled with a physical self-loathing that verges on body horror, and she is a virgin both compelled and revulsed by the thought of sex. She concocts absurd fantasies of the people around her, yet barely interacts with anyone; her interior life is not rich, but it is grotesquely vivid. She is like a minor character from a noir novel to whom the entire narrative is given over.

These thoughts and memories are mitigated from mere freakishness both by their inventive nature and by the tempering voice of older Eileen, occasionally assuring both the reader and her younger self that younger Eileen is taking everything entirely too seriously and that she will eventually begin to act like a woman more in control of her own soul. Thus we are spared this from truly becoming nothing more than an unenlightening exercise in the constant re-rehearsal of delayed teen angst, but Moshfegh’s inventiveness (Eileen isn’t as experimental as some of her other work, but it never lets us off the hook by telling us a completely normal story) is what allows it to transcend its own construction and become something special. Older Eileen both undercuts herself and subverts our expectations; we never lose the sense of creeping suspense that something is going to happen, but the early assurance that it will transform her into someone else keeps us forever wondering what, exactly, what it will be.

It is this voice that keeps Eileen from being merely an outlandish twist on (or, worse yet, a post-modern ‘homage’ to) classic noir. The stumbling nature of young Eileen fits the sometimes less-than-crisp prose, and her utter lack of motivation keeps us at arm’s length until the appearance of the hilariously named Rebecca St. John, whose arrival kicks the entire plot — such as it is — into high gear. St. John is almost more of a notion than a person, but Eileen’s infatuation with her is the trigger to the predictably dark fiasco that unfolds. (In this way, she is something like a shadowy mirror of the imaginary Boston gangsters that Eileen’s father, a drunken ex-cop, insists drove him into early retirement from the force, not his own incompetence and failures.)

Eileen sometimes seems to succeed despite itself. It burbles along, suffocating us with the intensity of Eileen’s perversion and insularity, but it is the way she keeps upping the ante on her own deviance that makes us stick around. The action puts us off again and again, failing to rise but merely humming along with a buzzing intensity, but it is the incisive bitterness of Eileen’s descriptions of her stifling surroundings (an unnamed New England seaside town) that forces us to stay tuned until the wavelength starts fluttering. For every moment the prose seems to flag — and Eileen is not the kind of novel that captures you from the outset with the razor keenness of its style — something about the sheer audacity of this portrait of a damaged woman, held in amber suspension and examined like a bug by her older self, makes it impossible to look away. It’s like that minor noir character, that librarian or waitress or clerk, turns out to have a much deeper and bleaker story than the doomed protagonist and the femme fatale put together.

By the time Eileen reaches its fevered conclusion, after a third-act turn that takes a while to arrive but justifies all the patience its narrative expends getting there, it has established a point of view and a character that is both flawed and unforgettable. Eileen is not a perfect novel, but the strange pivots and curious inversions that mark Moshfegh’s excellent short fiction are incorporated enough to give it a solid, if kinked, spine. It’s very unique and worth reading, and if it does nothing else, it will whet your appetite for Homesick for Another World.