I woke up this morning to have my vacation spoiled by lots of social media chatter about what a terrible job the American media, and in particular Matt Lauer (who is, I suppose, technically a journalist), did of handling Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump last night. Lauer was selected, by virtue of his familiarity to audiences, to speak to both presidential candidates at something called the “Commander-in-Chief Forum”, the very name of which suggests the degree of seriousness with which it should be taken; it was held at Manhattan’s Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, a tourist attraction run by real estate moguls.

The most common thread in this criticism was that Lauer, a pleasant cartoon who sometimes has its word balloons filled with the text of news items, created a ‘false equivalency’ by treating Trump, a thought-free blowhard who fires people on television, as if he were on the same level as Clinton, who is more serious by virtue of the way she expresses her bad ideas. This is a fair criticism, on a certain level. While I have myriad problems with Clinton as a candidate, as this review and essentially everything I have ever written about her makes clear, she is superior to Trump on a number of levels: intellectually, politically, and personally, to be sure, she makes him seem like the crass joke he is. But on another level, the problem is a deeper one: whatever their virtues, or lack thereof, Clinton and Trump are the candidates of the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively, and those parties are, by design, the only ones that are capable of winning elections at almost every level of American politics. If Trump is a buffoon, the fault rests less with Matt Lauer’s unwillingness to call him one than it does with the American public’s utter apathy towards electoral reform.

Ever since it became clear that Hillary Clinton would be the candidate of the Democratic Party in 2016 — that is, after no Barack Obama emerged to rob her of her destiny, and Bernie Sanders was banished for his stubborn insistence on making his political campaign reflective of his actual political beliefs — the idea that she is being treated unfairly (especially by the press) due to her gender has been inescapable. There is certainly some truth to this, as the double standard is alive and well particularly on the American right, and at any Trump rally or similar convocation of reactionary recidivists, misogynistic expressions of gendered hatred for Clinton are commonplace. But this has slowly transformed, particularly amongst a certain type of meritocratic liberal feminist, into the idea that any criticism of Clinton is an attack on not only her femininity, but on women as a whole.

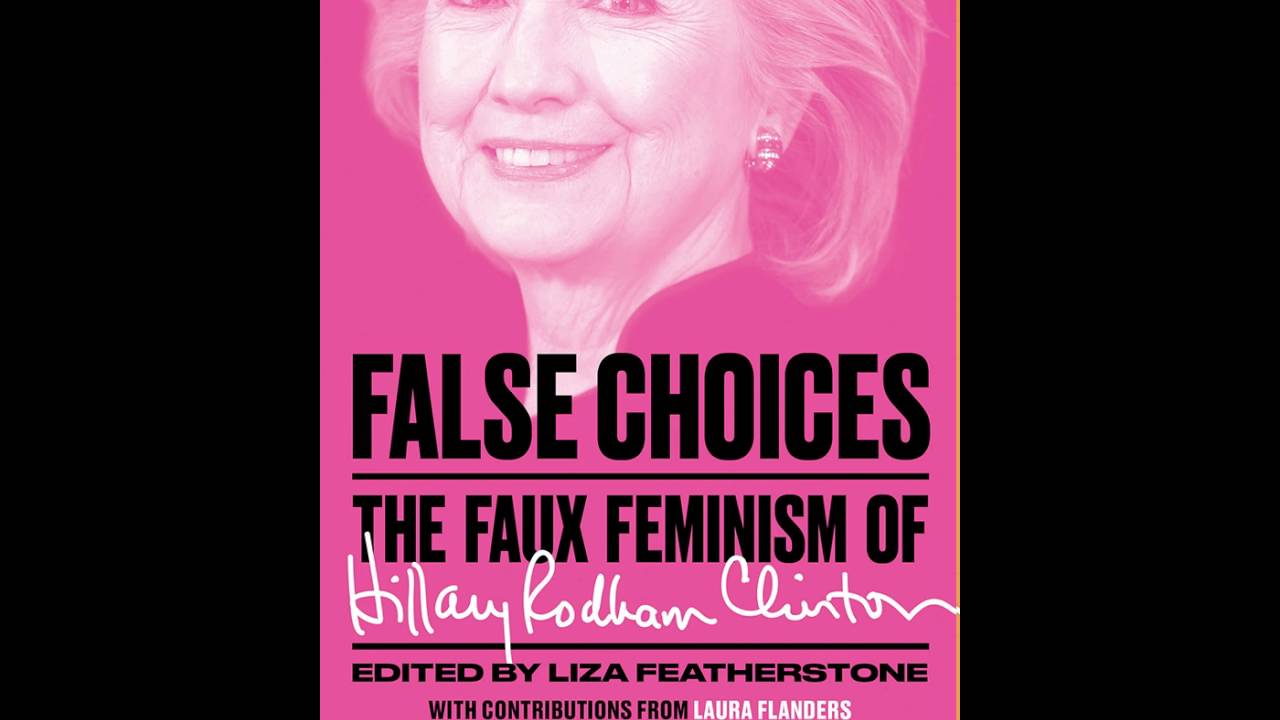

Enter False Choices: The Faux Feminism of Hillary Rodham Clinton, a small but powerful collection of essays edited by Liza Featherstone. The credentials of its seventeen contributors are impeccable, ranging from academics to journalists to labor activists to sex workers; and, contrary to the insidious narrative that socialist/leftist critics of Clinton are overwhelmingly young white misogynists, all but one of them are women, many are people of color, and they range in age from their early 20s to their 80s. All are feminists; all are liberals or leftists (again, despite the idea that socialist attacks on Clinton derive from right-wing FOX News talking points, this is the farthest thing imaginable from a conservative argument); and all are united in their belief that Hillary Clinton’s history and politics should be a clear warning that her presidency will be no triumph for the cause of women.

One of the most interesting things about False Choices is the plurality of its viewpoints. Not only is it a book written by women of different ages, races, and backgrounds, but its attitudes towards Clinton as a candidate range from mild discomfort (of the “grit your teeth and vote against Donald Trump” variety) to utter revulsion. Absolutely none of them, however, engage in anything that could be reasonably categorized as misogynist; indeed, almost every argument against a Clinton presidency is predicated on the idea that it would be bad for women. Some of these arguments are drawn from her past as a legislator and public figure; some make inferences based on her support of her husband’s record as president, which was disastrous for poor and minority women in particular; and others attack the very idea of a feminism based on merit, on wealth, and on the idea that there is something inherently positive about a women in power, regardless of her ethics or ideology.

Similary, there are a wide range of issues on which the authors find Clinton’s candidacy disturbing. Some are relatively familiar, such as her support of Bill Clinton’s welfare ‘reform’ and free trade policies, or her time on the board of Wal-Mart, during which she had nothing to say about the company’s labor policies that left working women impoverished and tolerated workplace harassment and discrimination. Others are surprising: Megan Erickson’s chapter on how deeply the Clintons are involved in the for-profit educational industry was both revealing and disturbing, and Margaret Corvid’s piece on Hillary’s attitude towards sex workers while she was Secretary of State was something I knew nothing about. Belén Fernández’s piece on Clinton’s backing of the coup in Honduras leaves no doubt about how closely she follows the realpolitik of her diplomatic mentor Henry Kissinger, and the chapter by Frances Fox Piven and Fred Block is False Choices’ most intellectually accomplished, spelling out in rigorous academic detail the origins and impact of neo-liberal welfare reform and how it has been a disaster for the poor.

The book doesn’t succeed on every level. The introductory piece by Laura Flanders is weak and tedious, hiding its good points behind a poorly executed one-sided dialogue. Catherine Liu’s essay on neo-liberalism, the immigrant experience, and her father’s views on To Kill a Mockingbird adds a welcome personal perspective, but doesn’t do much to build a political case against Clinton. And the book would have been greater at twice the length. But it’s a very good and very necessary read, especially as it becomes more and more clear that a Hillary Clinton presidency is inevitable. Appearing on the unmissable CHAPO Trap House podcast, editor Featherstone admitted that what surprised her the most wasn’t that False Choices was met with hostility or ridicule, but rather with indifference: even the most resolute mainstream defenders of Clinton mostly ignored the book. It seems that to this flavor of feminism, there really is only one choice, and holding your candidate to a justifiable standard of behavior isn’t part of the program.