I take Rosa Luxemburg very seriously.

Since feminism and class consciousness have been two of my passions my entire adult life, it’s easy to see why I’m drawn to women who vocally espoused both, and Rosa Luxemburg is perhaps the greatest of them all. I’ve read her writings, studied her life, and held her up as an exemplar of the kind of revolutionary socialism I’m drawn to ever since I first heard about her in college. When my best friend visited Berlin years ago, she took pictures for me of the train station named for Luxemburg and the statue that stands in her honor. Looking at her work today, it’s amazing how prescient her particular analyses of Marxism, capitalism, and economics are, and how relevant her critiques of politics remain to our present era. (She predicted the growth of globalism decades before anyone else, and with incredible accuracy; she also had mixed feelings about women’s suffrage, fearing that it would merely further empower the bourgeoisie.)

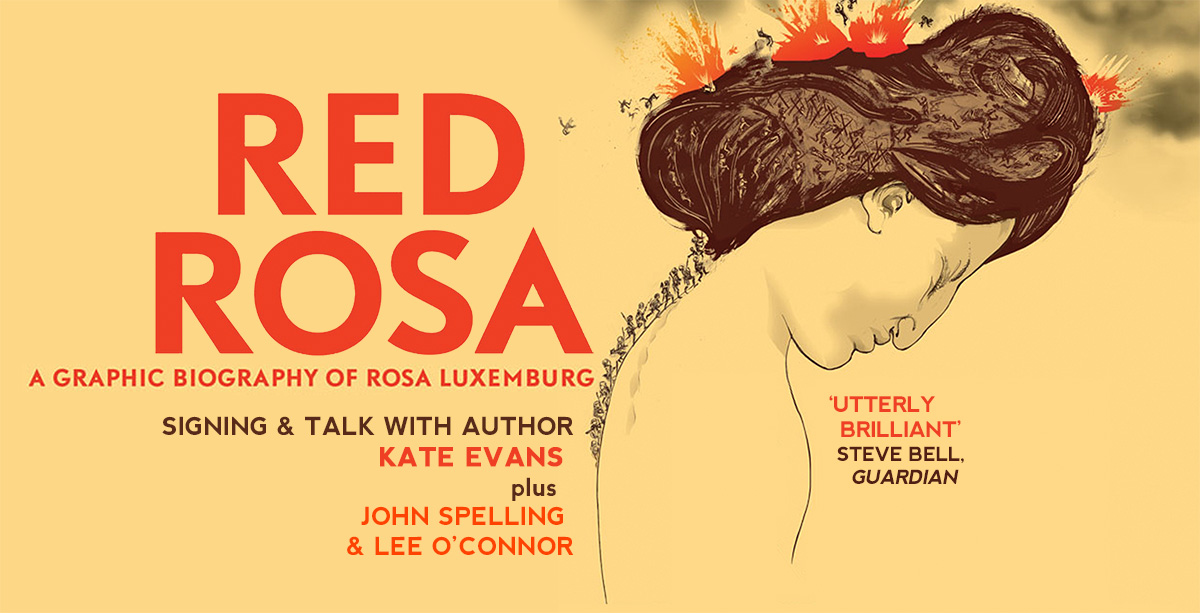

I also take comics seriously, which is probably why I don’t read that many of them anymore, but last week I was lucky enough to spot Kate Evans’ Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemborg at my local comics shop. I picked it up more or less on a whim, knowing nothing about the book, its origins, or the creator, but once I started reading it, it was nearly impossible to put down. It’s a powerfully successful effort, remaining scrupulously true to its subject while succeeding on its own terms as both a biography and a work of comic art. Evans has done a magnificent job here, not only of telling a well-researched story of a truly important figure of the left whose life is not nearly as well-known in America as it should be, but of avoiding — albeit, at times, somewhat narrowly — the pitfalls that many other books of a similar nature have made.

Luxemburg was keenly attuned to the contradictions of both capitalism and the Marxist critique of it; it’s one of the reasons her work is so critically important. So it’s entirely fitting that Red Rosa skirts the contradictions of modern comics biographies without ever collapsing in on itself. The most common of these problems, particularly when telling the story of a person who is best known for their ideas, is the trap of simply making your comic a series of talking heads, of vaguely sketched illustrations that are little more than a prop leaning in front of a wall of text. This can work, but the problem is, it’s not really comics; it’s really just illuminated text, and usually leaves one wondering why the illustrations were necessary in the first place. Evans, though, provides a beautiful visual element against which to set the story of Luxemburg’s life and ideas; while she does struggle on occasion, and there are a few pages where Rosa appears as a cameo in her own life, foregrounding excerpts from her own books, she much more frequently is able to find inventive ways to illustrate her subject’s ideas and beliefs, integrating them into a well-told narrative and breaking with standard biographical techniques through the use of clever visual metaphors.

Evans clearly cares deeply about her subject, which brings up another seeming contradiction: how do you tell an engaging story of someone you admire without it turning into hagiography? This isn’t so much avoided as it is fully embraced. She makes no bones about how important she considers Luxemburg as both a thinker and a person, but she’s able to bolster this with enough historical context and situational information that it seems to naturally extend from the text. And, frankly, there’s a huge amount about the woman to admire, which is why she deserves such a loving biography. She was principled, progressive, brilliant, rigorous, thorough, daring, and outspoken at a time when it was not just perilous to be a socialist, but to be a woman. She had to travel to a country entirely unfamiliar to her just to go to school, as her Polish homeland did not grant higher education degrees to women; but she did so, while still a teenager, and never looked back. (Alongside all her other achievements, her doctoral thesis on the industrialization of Poland is still the standard reference on the subject.) A few times, Evans actually breaks the fourth wall to expand on these events, a choice that has very mixed results but never fails entirely.

But for all its celebration of Rosa Luxemburg the thinker and the leader, it does not ignore the realities of Rosa Luxemburg the woman. Her childhood injuries that left her with health problems her entire adult life; her frequent clashes with other Marxists and with the political organizers of the German left; her love of animals and her playful sense of humor; and, especially, her often difficult love affairs with men are all depicted here, both romantically and realistically. One of the curious things about Red Rosa is that it alternates so rapidly between tragedy and comedy, but Luxemburg was a woman who loved life, embraced pleasure, and liked to laugh and tease, even when important matters were on the line. Evans knows that to deny this aspect of her subject’s personality would be to deny much of her essence.

For Rosa Luxemburg took the struggle seriously. We often forget, in an era when we seem more focused on microaggressions and the language of justice over the reality of it, that people like her literally fought and died for the freedoms we take for granted. It was almost a hundred years ago now that the Spartacus League she founded took to the streets in open revolt against the failed German government that had led the nation into a bloody, pointless war she not only opposed but predicted; while she thought the revolt was poorly timed and planned, she stood by its moral rightness, and she paid the price with her life, as did her friend and co-founder Karl Liebknecht, and her longtime lover Leo Jogiches, who was likewise murdered while investigating their deaths. Evans has given her an astonishing, effective, funny, playful, and fascinating send-off, and it serves as a vital reminder not only that Luxemburg’s Marxist critique is perhaps more important now than it ever was, but that Germany lost the chance to be led by her, and instead set the stage for the ascension of Adolf Hitler. I’ll let Red Rosa speak for herself in ending this review:

“Perhaps you will ask, is not submission to the vagaries of the market a small price to pay for individual freedom? Alas, how unfree is this worker here. The distinctive feature of capitalism is the precariousness of the worker. The capitalist controls the means of production; the worker has nothing. The only commodity he can sell is his labor power, and the entire process revolves around the exploitation of that labor. The worker may think himself free, but what choice does he have other than to sell his labor? Jobs are scarce and insecure, for the capitalist keeps a reserve army of the unemployed ready at his bidding. The capitalist certainly considers himself free; but what choice does he have but to press his workforce ever harder, driving up his profit? For if he doesn’t swim ahead of the competition, he will sink. All humanity groans with frightful suffering under the yoke of a blind social power — capital — that it has itself unconsciously created. The underlying purpose of every social form of production — the satisfaction of society’s needs — is turned completely on its head. Production is no longer for the sake of people; production for the sake of profit becomes the law over all the Earth.”