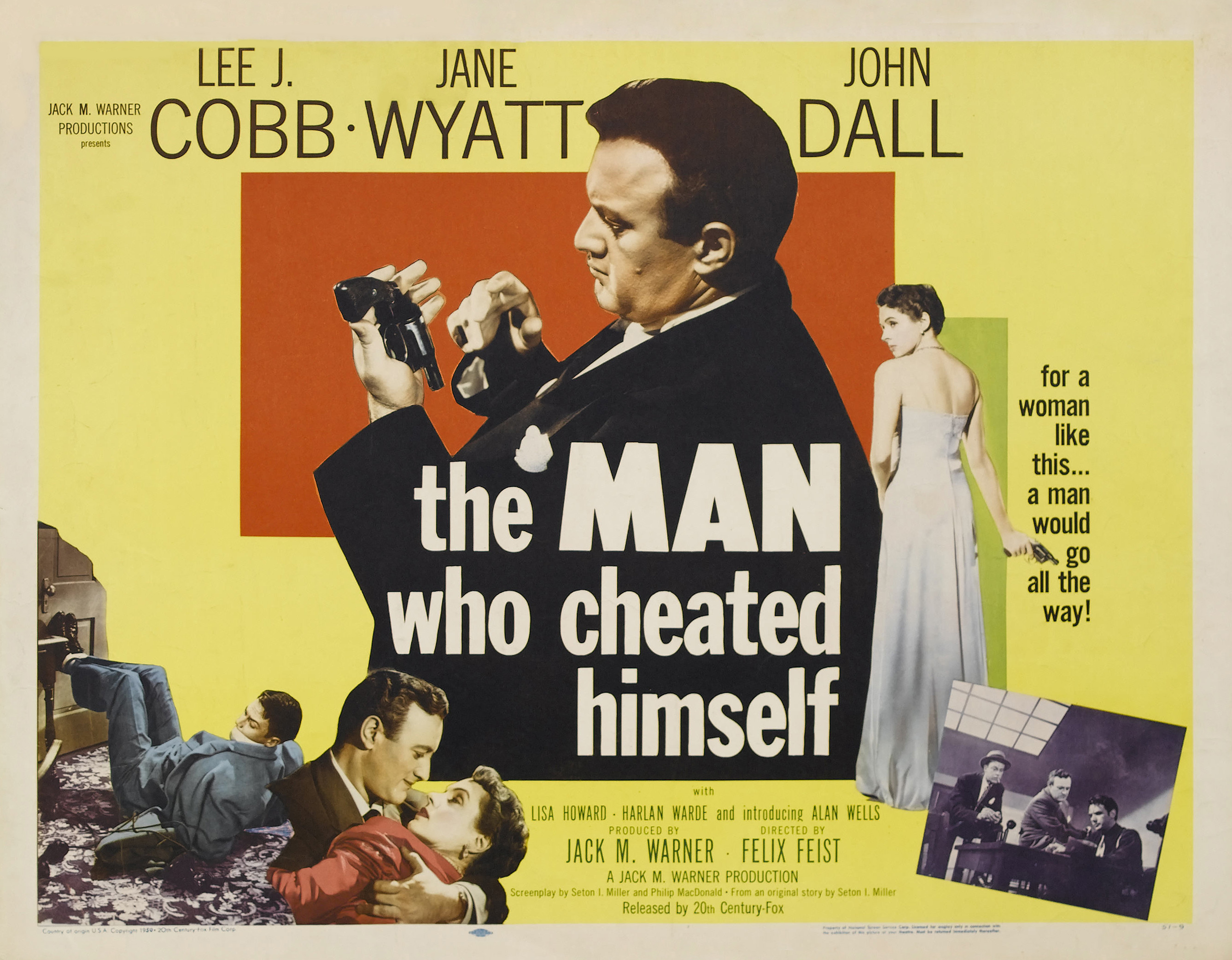

If nothing else, The Man Who Cheated Himself — released at Christmas in 1950 and capably directed by Felix Feist — is a good reminder of what, exactly, most noir films were supposed to be: cheaply made B-grade crime pictures to be stuck in second or third place before the main attraction. Although it was helmed by Jack Warner and released by 20th Century FOX, aside from a few flashy San Francisco location shots, it has the look of a Poverty Row picture; it looks like it was brought in for pocket change, and a scene allegedly set at a major municipal airport consists of one guy behind a single desk holding an airline ticket.

So it’s not going to win any awards for mise-en-scène, but there are still reasons to expect that Man will have its virtues: the writing team, for one, consists of veteran screenplay hand Seton Miller (responsible for, among others, Hawks’ Scarface, The Adventures of Robin Hood, and Ministry of Fear), and British mystery novelist Philip MacDonald. It may be the influence of the latter that accounts for the off-kilter feel of the flick: while it’s got all the individual components of a noir film, it plays for much of its running time like a more traditional whodunit. In patches, it seems almost like a drawing room mystery, with clues being doled out in a far too obvious way to the audience and bits of business that are entirely too on the nose. (The visual effects are handled by someone with the delightful name of Rex Wimpy.)

The Man Who Cheated Himself begins with what appear to be the meticulous preparations for a murder: social-climbing Lothario Howard Frazer (Harlan Warde) is seen carefully loading a revolver and gathering his papers as he prepares to walk out on his elegant but rotten wife, Lois (Jane Wyatt). The two have only been married three years, but they obviously loathe one another; after some pointed comments about Wyatt changing her will, Warde storms off, leaving us to clearly assume that he’s planning to off her. That’s when the plot delivers its first twist: Wyatt has been married a few times, and now she’s set her sights on a new beau: hulking SFPD homicide detective Ed Cullen (Lee J. Cobb). Calling him over to her low-budget fancy house under the guise of protecting him, Wyatt actually plans to do a little killing herself: when Warde returns, she unloads on him, filling him full of lead and leaving Cobb with a bloody mess to cover up.

At this point, it’s pretty clear that we’re supposed to accept Wyatt as a particularly heartless femme fatale: she’s rich, loose, vicious, and correctly assumes her chump of a boyfriend will try to get her off the hook for cold-blooded murder even though he’s an officer of the law. But Wyatt doesn’t really sell it that way; she plays everything so breezily that she comes across as more annoying than sinister. In one particular scene, Cobb warns his new partner about the consequences of telling someone that a loved one has been murdered: “Some cry. Some faint. But it’s the ones who just stare at you…” Wyatt doesn’t do any of those things; she acts like the officers have come to tell her that her car’s been stolen.

That new partner is Cobb’s brother, Detective Andy Cullen, played as a jangly, oddly appealing jerk by Gun Crazy‘s John Dall; he’s freshly promoted to Homicide from walking a beat, and he’s been placed under his brother’s wing, which gives the subsequent developments most of their kick. In fact, it’s the interplay between Cobb and Dall that saves The Man Who Cheated Himself; it’s not just the edge their relationship brings to the plot, but the fine interplay between them, that keeps it from being a complete mediocrity. As Cobb becomes more and more implicated in the crime, trying to pin it on an already-crooked hood who shot a shopkeeper with the same type of gun, Dall keeps tripping him up, finding more and more ways his brother is connected to the killing, even as he resists making that final, fatal connection.

Dall and Cobb don’t look much alike; Dall is a whip-thin, lanky young joker with a hip demeanor and a casual air, while Cobb is a thick slab of menace with a voice like molten lava and the attitude of a man who’s seen and done everything. But they go out of their way to mirror one another’s behavior, with Cobb joshing Dall about his new wife (Lisa Howard, Feist’s then-wife, who would go on to become a successful journalist before a tragic suicide) and Dall needling Cobb about having no woman in his life as he gradually discovers that there is one and she’s a killer; some of the funniest bits of the movie involve them identically dressed in high noir fashion, in trenchcoats and slouch hats, seated at opposite desks with their heels kicked up and chain-smoking cigarettes as they try to suss out the mystery when they’re actually opposing one another.

There are a few other minor pleasures to the film, including the aforementioned location shots, some nice cameo roles from veteran Hollywood C-listers, and a comic bit involving Charles Arnt and Marjorie Bennett as an old married couple who discover Warde’s body. It’s hard to see much of The Man Who Cheated Himself‘s visual appeal; it’s in the public domain, and there’s apparently only existing print, a terrible transfer that skips, pauses, blots out the contrast, and has absolutely abysmal sound, full of pops and cracks and so muted you have to crank it way up to hear the dialogue. (It helps reduce the intrusiveness of Louis Forbes’ dull score, but that’s a pretty minor virtue.) While it’s not a total loss, the movie can never quite decide what kind of tone it wants to take, and wounds itself irreparably by putting Cobb’s implacable tough guy opposite Wyatt, who is merely aggravating when she should be ruthless. Even in the final sting, when Cobb is getting ready to pay for his crime and spots Wyatt cozying up to her attorney with the promise of wealth and romance if he can get her off, his expression is less of a classic noir protagonist doomed by his own bad choices than it is a beleaguered guy thinking “Can you believe this broad?”