Hetty Green was one of the first women to make a killing in stocks. The heir to a considerable whaling fortune, the dour and grim New England Quaker increased her net worth more than tenfold with canny investments in everything from real estate to railroads to war bonds, and when she died in 1916, she was the richest woman the world had ever seen. She was also notoriously stingy; her own son had to have his leg amputated because when it was broken, she frittered away precious time trying to have him treated for free at a local charity hospital, even though she was worth hundreds of millions in today’s dollars. For a number of reasons — her creepy demeanor, her uncanny ability to predict the markets, and good old-fashioned misogyny — she was nicknamed “The Witch of Wall Street”.

When I first heard about The Wolf of Wall Street, the latest offering from Martin Scorsese, I briefly thought it might be about Hetty Green; now that I’ve seen it, I wish it had been. Of course, it’s a cardinal sin for a critic to talk about the movie he wishes he’d seen instead of the movie he actually saw, but Scorsese sorely provokes the temptation these days. I used to think of him as the greatest living American filmmaker, a title that I think he’s long ceded to the Coens; what mostly stands about about him today is that it’s more interesting to discuss the critical reaction to his movies than it is the movies themselves. This is a bad scene for everyone involved. Once any artist in any medium becomes more of a creature of the media than an inhabitant of their own art, it’s a huge caution lamp being lit, and though it’s often accurate to blame the critics for the state of affairs, that’s not the problem with Martin Scorsese anymore.

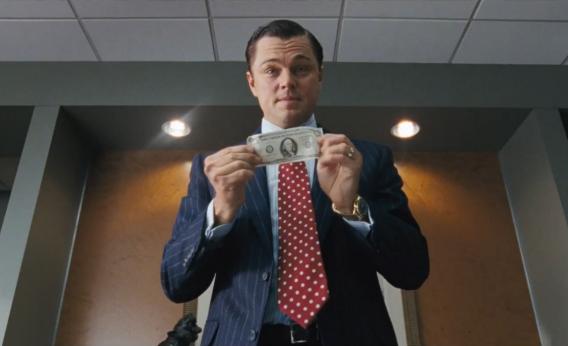

The reason why is that his films have begun to resemble performance art rather than acts of filmmaking, leaving us to contemplate what should be irrelevancies rather than what’s present on the screen. Watching the story of boiler-room swindler Jordan Belfort (portrayed by a powerful but never especially engaging Leonardo DiCaprio, who never seems to be his own age), we care much less about his life and times than we do about what might have motivated Scorsese to tell his story. That’s not something we could say about Jake LaMotta or Henry Hill, characters whose inner life and outer conflicts were always so present as to seem to be burning up the screen, but Scorsese doesn’t really seem like he’s been all that interested in a narrative film since Gangs of New York. (His documentaries are a different matter, for a different review, but it’s telling that he’s more engaged with the real world as he’s drifted away from caring about story.) This detachment seems to be contagious, as no one on screen — with the exception of Jonah Hill, whose dramatic chops seem to be growing with every role he takes — is particularly engaged with the movie either.

This isn’t to say that Wolf is a bad movie. Scorsese has enough craft and dedication that the likelihood of him ever making a genuinely bad movie is close to zero. It’s a gorgeously assembled movie, full of incredibly cinematography, clockwork editing, powerful rhythms, and scenes that move so muscularly and confidently that you can’t help but be drawn in. It never seems bloated, even though it’s easily too long by half. There are probably half a dozen moments you could pull out of it and stick into a highlight reel to back up my long-ago assumption that Scorsese is as good as American directors get. It’s just that — well, we’ve seen it all before. I don’t think the idea that this is Scorsese remaking GoodFellas for a new generation is particularly credible (he didn’t need to; stock frauds of the sort that Belfort engaged in were heavily mobbed up), but he’s certainly not showing us anything new; he’s pulling out bits from his greatest hits and ramping them up with new technology just to prove he can do it, to show the kids who have spent 20 years stealing his act that he still does it better than anyone. It’s performance art. Which is all well and good — the instinct to bristle up and swing for the fences must be powerful at that age — but there isn’t a moment in the whole movie where I thought Scorsese cared a tenth of a shit as much about Jordan Belfort as he does about Mick Jagger.

That lack of commitment to the material carries over into what has, curiously, become the movie’s biggest talking point. The charge that Scorsese doesn’t do enough on screen to condemn the moral failings of his subject is pretty silly, and the accusation that he glamorizes Belfort’s misdeeds would carry a lot more weight if you hadn’t seen pretty much every other movie the man has made with the possible exception of Kundun. Scorsese is well aware of what he’s doing and the kind of waters he’s swimming in, and generally, he trusts the audience to know what lessons should ultimately be drawn from his stories, whether it’s GoodFellas, The King of Comedy, or Taxi Driver. But if anyone leaves the theater, especially now when the country may have suffered a fatal economic blow from short-takers of Belfort’s stripe, thinking Scorsese hasn’t come through with a powerful enough referendum of his character, it’s not because he doesn’t understand or appreciate what Belfort has done; I think he just doesn’t care enough to let it show. Scorsese was obviously deeply engaged in both the highs of Henry Hill’s gangster life and the lows of his eventual downward spiral; I never once got the impression that he (or Leonardo DiCaprio) were particularly interested in the moral arc of Jordan Befort’s career.

At this point in Scorsese’s career, he’s literally got nothing left to prove, which is both a blessing and a curse. He could have stopped making movies 20 years ago and still be considered one of the greatest talents ever to lens a film. It’s meaningless to ask, even in light of a flawless failure like The Wolf of Wall Street, to ask how many great movies the man has left in him; he’s got nothing but great movies left in him, as many as his health will let him make. It’s just that we’ve seen a lot of them before. For him to return to making not just great movies, but great movies that matter, we’ll have to find a definitive answer to the question: are there subjects for narrative film that engage his mind the way he wants them to engage ours? For all its considerable strength, Wolf answers that question with a resounding “not yet”.

Pingback: Leonard Pierce Reviews The Wolf of Wall Street | Screengrab In Exile

I like it, though I disagree with your assertion that Henry Hill is a “character whose inner life and outer conflicts were always so present as to seem to be burning up the screen.” He was plausible, sure, but he struck me as the least interesting character in Goodfellas. Not necessarily in a bad way, mind, but I figured he was more a lens into a fascinating world than a character with a compelling viewpoint. In this way, he was similar to diCaprio’s character in Gangs of New York.

I had a better sense of who Jordan Belfort was than who Henry Hill was, although the question on which most of the first act hinges – what exactly turned him from an idealistic, eager-to-please junior trader into an amoral sybarite – is never really answered.