Charles Mingus is wrong, you see.

Mingus is the first (and the greatest, though he’ll have some stiff competition) jazz musician we see, idly coaxing some low mournful notes out of his upright bass in the spacious London loft of jazz aficionado Rod Hamilton (played with maximum glad-handing by Richard Attenborough). When Dickie notes that he’s the first one to arrive, Mingus replies that he’ll be the last one to leave, but it’s not true. Events will take a very different turn.

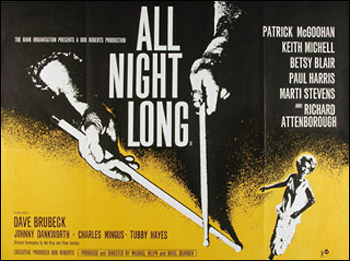

The “here” in the “first one here” is a surprise one-year anniversary party for newlywed jazz musician Aurelius Rex (Paul Harris) and his wife, vocalist Delia Lane (Marti Stevens), who has given up show business to be with him. Hamilton has gone all out, throwing the kind of blow-out we all feature in our dreams: located in a huge, spacious, and inviting area with smart, funny, attractive people who all take turns on stage showing off their musical chops. Many of the guests are American and British jazz heavyweights playing themselves, most notably Mingus, Johnny Dankworth and Dave Brubeck, and it’s a treat to see them playing alarmingly good music as if it was just a way to screw around between cocktails.

Also among the invited guests are sax man Cass (Keith Michell) and the drummer in his band, the manically energetic and ambitious Johnnie Cousin (a terrific Patrick McGoohan). Cousin wants to strike out on his own, and he’s got talent to spare — and even more ego. (He brings his own kit at great effort rather than use the one Rod has sitting around the loft; “yours doesn’t have his name on it,” explains another partygoer.) But his is just one of a hundred bands trying to make it; the king-making record producer of the moment is only interested in signing and promoting Johnnie if he can make good on a promise to bring Delia out of retirement and have her front his band. The primary obstacle to this is Aureliuus, a sullen and possessive husband who thinks the strength of his marriage depends on keeping her at home. So he sets out to plant doubt in Rex’s mind, hoping to trash his marriage and leave Delia free to return to show business.

If all this has a familiar ring, it’s because it’s based on one of the most venerable stories of the western canon — it’s no more or less than an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello, set in the jazz milieu of ’60s London. If there’s one kind of movie for which I’m a total mark, it’s off-kilter takes on Shakespeare, and I’ve seen the good (Michael Almereyda’s underrated 2000 big-business Hamlet, Kurosawa’s Ran), the bad (Baz Lurhmann’s hyperactive Romeo + Juliet, Joss Whedon’s all too broad Much Ado About Nothing) and the weird (O, the high school basketball version of Othello, and the small-town burger joint version of Macbeth that is Scotland, PA). All Night Long is unique in a certain sense: while most modern updates of Shakespeare attempt to ramp up the impact by throwing in sex, gore, and even more dead bodies than feature in the originals, it drastically lowers the stakes and asks the not unreasonable question “How would Othello have ended if everyone in it acted sensibly?”

All Night Long was directed by Basil Dearden, and I saw it as part of the “London Underground” box of his films released a while back by Eclipse. He displays his usual tight, quiet competence here, but it’s not entirely free of flash; there are a few moving overhead shots, giving us a god’s-eye view of the party, but since that seems like exactly the way you’d want to enjoy that kind of a party, it’s not too much of distraction. His camera eye is fluid and constantly moving, like a dinner host flitting from guest to guest making sure everyone is enjoying themselves, and he lets the music and the actors do all the heavy lifting. In the former case, his instincts are never off; it is in the latter that he’s let down a bit. Few of the jazz musicians seem all that at home speaking lines to a camera, but Dearden only lingers on them when they’re playing; a few members of the cast, however (especially Michell), seem a bit at sea. Others, though, deliver the goods; a great minor role as Michell’s bandmate and sometime lover goes to Maria Velasco, and McGoohan is fantastic, alternating between self-loathing and cockiness. (He’s also a hell of a drummer.)

Another area where Dearden veers away from the norm of Shakespeare adaptations is the reality of Rex and Delia’s marriage, for he is a black musician and she a white singer. Their pairing wouldn’t have generated as much controversy in 1962 England it would have in the U.S. (particularly in the South), but it was hardly a subject that everyone would have been entirely comfortable with, either. Most takes on Othello greatly play up its racial elements; even Shakespeare makes a big deal out of it. In All Night Long, it hardly seems to be an issue, presumably because all of their friends are jazz musicians, and wouldn’t make it far in that career if they were openly hostile to blacks. But that’s a surface reading only; it is enriched by a look beneath, at a subject too often erased by modern readings. For Rex, like Othello, is not a particularly nice man, even before the relationship with his Desdemona turns sour. He is proud, violent, suspicious of his own good fortune, and entirely too aware of the way his skin makes him an outsider in the world he has chosen. Iago (or here, Johnnie) may be the straw that stirs the drink, but it wouldn’t be such an easy thing were not his target already inclined towards wicked thoughts, were he not as self-conscious as he is talented, were he not so distrustful of his relationship. Delia may protest that it was her idea to quit performing, but what sort of a man so rapidly accepts that offer? In this way the racial issue is sublimated, but never entirely gone.

This all plays out with a considerable degree of sparkle and conviction. When Johnnie’s lies are exposed (largely with the help of his miserably devoted punching bag of a wife, excellently assayed by Betsy Blair), Rex and Delia’s marriage seems to be saved, but is it worth saving? There’s no small amount of ambiguity about whether it’s the right conclusion and not just the happy one. Johnnie’s downfall — preceded by a confrontation with his wife which he punctuates with stabbing riffs on his drum kit, each one delivered like a physical blow — culminates with the realization that it is he, and not Mingus, who is the last to leave, and All Night Long ends with him alone, furiously flailing at his instrument, his ambition having outstripped his talent for good, casting an empty shadow on the wall of the loft. In the hands of a lot of directors, this would come across as beyond hokey, but Dearden manages to rescue it and turn it into something memorable and not just remembered. His reputation was got with merit, and won’t be lost deserving.