One of the great losses of the Internet age is the legendary quality of the you-had-to-be-there moment. Once upon a time, it was possible to evoke the unrepeatable glory of some event, some concert or performance or speech, and assure your audience that it was a thing of transcendent greatness, forever lost except in the memories of those lucky enough to witness it. Now, with the ubiquity of Twitter, camera-phones, and cheap digital audio and video recordings, we have the good fortune of being able to see and hear everything there is to be seen and heard; but what we have lost is that great mystery of exclusivity, of being one of the fortunate few who was really there, and really saw what others can only imagine.

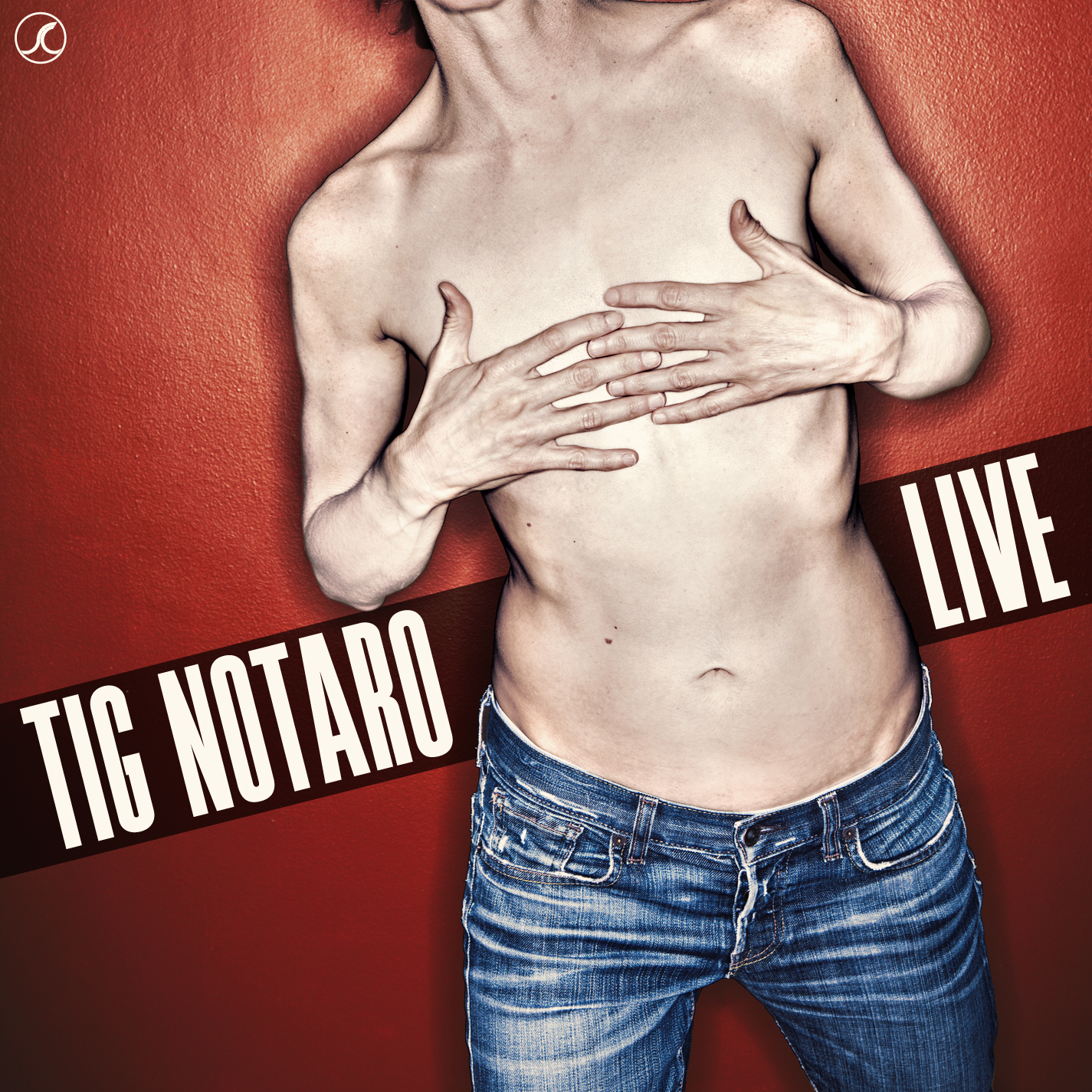

Thus it was with some trepidation I received the news that Louis CK was releasing, through his website, an audio recording of a brief comedy set by fellow comedian Tig Notaro. Only two months ago, Notaro delivered the set at Largo in Los Angeles; it instantly attained the status of legend. Notaro, already one of the finest stand-ups in the business, had just gone through a series of unthinkable tragedies: she’d been struck with an intestinal disorder that nearly killed her; her mother died in a fall; her girlfriend dumped her; and, literally days before the Largo show, she was diagnosed with cancer in both her breasts. The half-hour set she delivered dealt frankly with not only those subjects, but her own reaction to them — and perhaps most importantly, with the reaction of her audience. It was said to be so stunning that almost everyone who attended, including CK himself, marked it as one of the great moments in the history of the medium.

And that’s exactly why I got nervous. Once the legendary becomes commonplace, once something rare and difficult becomes everyday, it often loses its luster. A great concert may turn out to be perfectly ordinary listening for someone who wasn’t there to be spellbound by the unique energy of a live performance; a great novel, long out of print, may prove to be rather dull when viewed without the lenses of nostalgia. It makes me a terrible cynic to say so, I know, but when the Notaro show went on sale, I knew I would buy it, but I was consumed with dread that it would fall far short of its reputation, that it would prove to be another simply adequate thing inflated to legendary status by those who were there.

I shouldn’t have worried.

Live (used here as a verb, not an adjective) is an extraordinary, marvelous, almost unbelievable performance. Nothing I had heard about it, no matter how specific and hyperbolic, could have prepared me for how wonderful it turned out to be.

Notaro has always had incredible timing and pace — as I’ve written elsewhere, she uses silence the way a great musician does, dropping in her punchlines and recalls where they do the most possible damage. She’s also a hugely efficient manipulator of her audiences, reading them quickly and then playing them like a violin, suckering them in with misleads and deceptions only to clobber them with clever reversals. For sheer craftsmanship, she’s almost unbeatable amongst contemporary comics, delivering devastatingly minimalist sets where others fill up empty space with clutter, repetition and noise.

But in Live, she goes leagues beyond anything she’d done before. Using her same sense of time and her same ability to scan a crowd, she kicks everything into fifth gear and quite simply has the audience on its knees and eating out of her hand — which is all the more astonishing when you consider what her own emotional state must have been like. She talks during the set about her own lack of drama, her inability to get as worked up over things as she should, but all kidding aside, that quality serves her here like almost nothing I’ve ever heard. She practically keeps the audience in terror, while quietly poking them about it the whole time, asking them what they’re so upset about, assuring them — her, assuring them! — that everything is going to be all right.

I’ll be honest: Live is not the funniest stand-up comedy you’ll ever hear. There are recordings with far more and bigger laughs per minute; even Notaro herself has been funnier than she is here. Which isn’t even remotely to say that it isn’t funny; there are a number of flat-out howlers here. Her discussion of a ‘customer service’ questionnaire sent to her dead mother is fantastically funny, and a bit where she attacks the old “God never gives you more than you can handle” is both hilarious and punishing. But what’s truly astounding about Live isn’t the comedy, good as it is. It’s the spellbinding way Notaro holds the audience (and, by extension, the listener) in thrall as she talks through the horror show her life has become in a way that is both unexpected and completely natural.

There is nothing in the performance that seems forced, but it is also unique in its approach. We are simply not used to hearing people talk this way about illness, disease, and death. There is no clichéd moment of triumph; every time Notaro drifts near anything life-affirming or inspirational, she torpedoes it. But it’s also not a bitter, nihilistic fuck-everything approach, something that an angrier comedian, more confident in his righteous vision than his craft, might deliver; this is the same Tig Notaro, giving the same Tig Notaro routine, but about something no comedian ever wants to talk about except in the abstract. She even pokes holes in other ‘funny’ approaches to cancer, such as banal greeting cards; when a friend assumes she knows all about them, she boggles at the idea that her disease is just a new subculture, like she’s getting into ska. (I know I’m not making all of this sound funny; believe me, Notaro takes care of that end just fine on her own, leaving me to tell you how blisteringly great it is as a performance.)

Late in the show, wondering if she’s just bummed everyone out, Notaro asks the audience if she should just get back to her regular material. In what’s become one of the set’s legendary moments, the crowd loudly responds to the contrary, with one guy clearly saying “This is fucking amazing.” It didn’t need to be said; surely everyone in that room knew how fucking amazing it was. But it confirms what was really happening that night in August: Notaro was not delivering anything like a normal stand-up routine. She was doing what the title of the official release suggests: she was on stage, living. She was doing what makes humanity unique: she was using those special quirks that only our brains possess — abstraction and self-awareness — to tamp down the ugly realities of mortal life. She was practicing irony in its greatest, most Rortian sense: as a tool to bridge the gap between people who cannot otherwise understand one another, as a means of creating empathy where none previously existed.

Good standup always does more than make you laugh, but great standup, as with all great art, makes you feel the importance and vitality of being alive. It is the easy way out to approach disease, despair and death as pathetic inevitabilities that make hash out of all human aspiration; but Tig Notaro, in Live, does something far more difficult and far more praiseworthy. She uses her living human mind to dance around those miserable, inescapable certainties and make them seem ridiculous, while never pretending they can be ignored. She manages talk about the brutal reality of death in a voice charged through to the core with life.