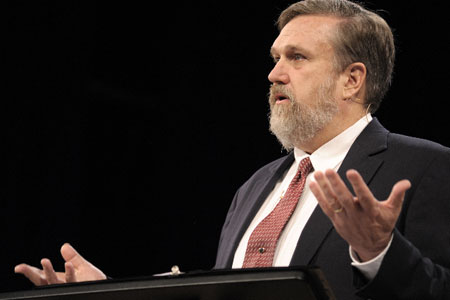

That well-fed fellow up there is the Reverend Douglas Wilson. A product of Idaho’s state university system and a recipient of the largesse of his flock, this noble sky pilot is best known for his series of debates with the notoriously godless Christopher Hitchens on the topic of whether or not Christianity has been a boon for mankind. (Rev. Wilson wore Jesus’ home colors in this debate, the answer to which I suppose depends on who you’re asking. He ought to be more famous, or infamous, for a monograph he wrote suggesting that the American slave system did a bang-up job of improving race relations in America, but let that one drift.) Anyway, here is what he has to say about organized labor, which we, as a nation, allegedly celebrate today:

“Organized labor is organized to take control of an asset away from its rightful owners without paying for it. Organized labor is organization of property by those who don’t own it. Organized labor, by driving up the costs of production through coercive means, destroys industries. Organized labor is piracy without the boats and eye patches. Why would anybody want to celebrate organized labor?”

Spoken like a true boss — or not even a boss, but one of the plentiful toadies of capital with which the Republic is blessed in these, the turbulent years. Wilson’s statement has what we in the semiotics racket like to call ‘definitional issues’, which is to say that he is using words to mean something different than they are usually supposed to mean — starting with ‘asset’, moving on to ‘rightful’, ‘paying’, ‘property’, and ‘own’ before moving into a pleasant little fantasia about workers destroying industries (what actually destroys industries is other industries). While his view of organized labor is perhaps a bit more vivid and virulent than usual, it is by no means uncommon; it’s echoed in substance if not in style by everyone from high-ranking Republicans to what the Wobblies used to call FWs — fellow workers who ought to know better than to stand up for the big shots. In pursuit of what they clearly hope to be the long-awaited final destruction of the union movement, conservatives have even stolen the language of their enemy: even from the likes of vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan, one rarely hears the word ‘union’ unaccompanied by the word ‘thugs’ — a word once used by the unions themselves to describe the armed goons dispatched by the bosses and their cronies in government to destroy worker organization by force.

Unfortunately, in order to dispel the sort of nonsense peddled by these valiant knights of labor-bashing, one is often obliged to use the language and theory of Marxism, which means, in this country, that one might as well be pausing every few minutes to hail Satan. Rehabilitation is a funny thing: Jesus may be forgiven for the innumerable sins of His church; Reagan’s hands are clean of the blood spilled by his anti-communist proxy wars; and even a butcher like Chiang Kai-Shek can be made into a hero if his opposite number is sufficiently vile. But Karl Marx will be forever responsible for the likes of Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot. Any quick-lipped Libertarian cowboy can cite you chapter and verse on the crimes of the state under Communism, but few Americans have even heard the phrase “White Terror” and fewer still can tell you what it means. You will search the mainstream political debate in this country in vain for any mention of the human and environmental horrors wrought by capitalism, imperialism, nationalism, or colonialism, but socialism will be forever joined with the gulag, the killing field, the cultural revolution. In the land where capital is king, the man who wrote Das Kapital is saved from being History’s Worst German only by the existence of a commie-bashing Austrian immigrant.

The more reasonable defenders of wealth will assure you that this is not a personal matter, but a practical one. Communism and socialism — they are leagues apart in reality, but one and the same in the propaganda of the free marketeers — have failed, you see. The proof of this is Mother Russia, where a terror state practicing economic central planning — condemned since its conception by millions of socialists all over the world — did indeed fall apart after a mere 72 years, no longer able to keep up with the reckless deficit spending of its enemies. China, meanwhile, thrives, having adopted a sort of fascist corporatism decades ago that is mightily appealing to American businessmen despite the saber-rattling of their representatives in Washington. North Korea stumbles blindly, a walking corpse held up by international aid, with its mutated neo-Stalinist totalitarianism, which not even the old men of Beijing take particularly seriously; Cuba soldiers on despite our frequent and comic attempts to destroy it, and at times seems to hold on out of pure spite, to show that the U.S. can still be made a fool of. Much of Europe, meanwhile, continues with decades of successful democratic socialism; despite bumps in the road here and there, much of western Europe, Scandinavia and the United Kingdom discovered ages ago that it was possible to get capitalism’s chocolate in socialism’s peanut butter without the world coming to an end.

And so it is that we celebrate Labor Day again in America, while holding labor in our usual contempt and disdain. Romney/Ryan is the most anti-union ticket since the Reagan Era; they have managed, even, to pull off a trick no one thought possible, especially in the post-9/11 era with its fetishization of emergency workers: they have demonized teachers, policemen, and firemen as leeches and moochers, no different from those brutes and extortionists loading our trucks, mining our coal, and driving our buses. With jobs being shipped overseas, reduced, reordered, made temporary, and flat-out eliminated every day, unions are at their weakest point since before they existed; conservatives are hammering away at public sector unions — labor’s only concentrated strength — as if it were that one last cockroach they haven’t managed to kill. Ironically, the bosses have learned many of the lessons of André Gorz — temporary work crews, project-based labor, a lessening of full employment in the wake of new technological advancements that require less productivity — but have ignored the most important one: providing some semblance of social welfare for those workers minimized and marginalized by such major shifts.

It is in this direction the free-market ideologues have forever been pushing the economy, because it is perfect for their vision of pure capitalism: a small and extremely rich ownership class at the top, and millions of workers, made abjectly loyal by desperation and deprivation, at the bottom. It is a return to slavery, with the slaves paying for their own upkeep and all too willing to be owned. And it is sustained by the fact that temporary success has led many in the middle to join their voices to the chorus of anti-worker rage. The successful entrepreneur and the middle-class striver with a good job and ample benefits have proven depressingly susceptible to the doctrine of I-Got-Mine, and too few are beginning to see that, after an economic downturn, a stock market collapse, or a round of layoffs in a weak job market, they’re in the same boat as the working men and women they used to look down on. Liberal identity politics have hurt rather than helped this trend; many minorities, women, and gays, elevated to new success, have bought into to the lie of a classless society, but as the seats at the bosses’ table grow fewer, they will learn the hard lesson that poor white trash learned ages ago.

Labor, then, is the question, and labor, still, is the answer. The great lie foisted on America in the post-Clinton era of free trade and the ‘post-industrial’ economy is that we have moved past the need for unions. Trade unions in America are in an untenable position, we are told, because it is now possible to ship everything from garment work to tech support to China, to India, to southeast Asia and Central America. Job specialization, high technology, the spread of professionalism and certification, and the rise of the service sector: these, too, are forwarded as reasons why solidarity against the bosses can no longer save us. Just like every other reason not to organize, of course, it’s all the bunk. Shipping jobs overseas, far from a reason to abandon unionism at home, is a reason to spread unionism abroad. If we help build strong labor organizations all over the world, the bosses no longer have an advantage in outsourcing domestic work — and our brothers and sisters in the developing nations get a taste of what our own struggles have earned us. The idea that specialized labor obviates unionism is a joke to anyone familiar with the innumerable specialized trades that found a home as part of larger industrial organizations. High technology and professional fields are no different from any other highly paid labor (such as players’ unions in sports) or intellectual labor (such as writer’s unions in Hollywood); these unions thrive even in bad times, and so, too, could tech workers and professionals if they weren’t so short-sighted. And service industry unions have grown by leaps and bounds; the immense power directed at slowing them or eliminating them illustrate their strength, not their weakness.

All workers — and non-workers, too; the number of unemployed Americans is more than double the membership of the five largest labor unions in the U.S. combined — must do is join together with their brothers and sisters, and fight. There have always been more of us than there are of the bosses, and there always will be; if we practice solidarity, there is nothing we cannot win, no injury we cannot treat, no privilege we cannot turn into a right — not just for some of us, but for all of us. The fat cats, and their bootlicks like the Rev. Wilson, like to pretend that labor unions are some alien excretion, some carbuncle on the purity of the market, some foreign body that invades the benign corporation and colludes to do it harm; but all organized labor wants is the same right to stand together as organized capital. Ever since the dawn of capitalism, the owners and bosses have banded together to lock in higher profits, gain more favorable market conditions, secure stable price structures, open up new areas for trade, and use their collective strength to get better prices on raw materials. This, carried out under the name of industry groups and trade organizations, is considered perfectly acceptable. But when working people band together for higher pay, better working conditions, pensions, wage guarantees, and improved benefits, they are treated as if they are pirates and theives, committing a heinous crime against society.

Adam Smith, the philosopher of capitalism much beloved by those who have not actually read him, had something to say about this hypocrisy. “Our merchants and masters complain much of the bad effects of high wages in raising the price and lessening the sale of goods,” he wrote in The Wealth of Nations. “They say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits. They are silent with regards to the pernicious effects of their own gains. They complain only of those of other people.” The conflict between capitalism and socialism, despite the claims of ideologues on both sides, is not absolute; it is only that one pushes the ludicrous idea that we are a world of six billion individuals, each self-contained and possessed of full knowledge of the world and its ways, one Objectivist pamphlet away from total autonomy and immunity to coercion and control. The other is predicated on the rather obvious belief that we all live in societies, and our fates are shaped by events within those societies that we cannot control on our own. For some such events, we need the power of the state to help us when we are beyond help, to boost us when we lack the ability to climb. For others, we need the power fo the union, to place the power of numbers against the power of money, to put the people who make the profits on equal footing with the people who take the profits, to make the economy subject to something more than caprice and charity.

Remember thisLabor Day: if you make good money and have good benefits, even if it’s not in a union shop, you owe it to the unions for standing up to the bosses; you didn’t earn what you’ve got because they like giving money away. If you have bad work or no work, you won’t get better by keeping quiet about it: stand up every day and shout out that you are ready to earn, and you’re not being given the chance to do so. It is always in the best interest of the bosses to keep you distracted, keep you separated and arguing amongst yourselves, fighting over crumbs instead of noticing the size of the pie. Lean times — and we’re sure as shit in them now — are not the times to give up on solidarity; they are the times when solidarity is needed the most. Every minute we’re spending correcting each other over who built what, we could be coming together to build something new. Don’t think party is the way out, and don’t just change one set of bosses for another. If you think the union movement is dying, do what Joe Hill said: don’t mourn, organize!