Dealing with the death of famous people is an emotionally thorny proposition. No matter how much you might have cared for their work, you didn’t really know them, and it seems almost intrusive to mourn them the way you would a friend or a family member. And, of course, death comes for us all, and most celebrities led perfectly comfortable lives, and accomplished a great deal, before their numbers were called, so it seems a little impertinent to call it a tragedy, or even a loss, when someone with an extensive body of work becomes an extensive body of work.

Then again, is it our fault that we live in a highly mediated age, or that we sometimes succumb to the relentless attempts by publicists and marketers to make some distant, faraway creative force seem like a part of our everyday life? Are we really to blame if we accept the fact that in a fragmented world where we spend half our lives struggling to live through the other half, we occasionally embrace the removed idea of a person the way we do a real person, that we take the loss of a life that we have voluntarily made a part of our world as the same brunt blow we would a family member we never see, or a friend we barely remember?

Worse, too, when that death truly does come too soon. We all dig our own graves today, but until the first scold whose idea of a good time is to shake their head in manufactured sadness at the habits that are going to kill everybody but them turns out to be immortal, we’re all digging to the same depth, if not at the same rate. No sooner had the word come that Kim Thompson, the co-publisher of Seattle’s Fantagraphics Books, died of lung cancer today at the age of 56, than we also were asked to cope with the heart attack death of James Gandolfini, the powerful actor most widely known for his role as conflicted mob boss Tony Soprano. Either death would have been an injury; both together were like a kick down a flight of stairs.

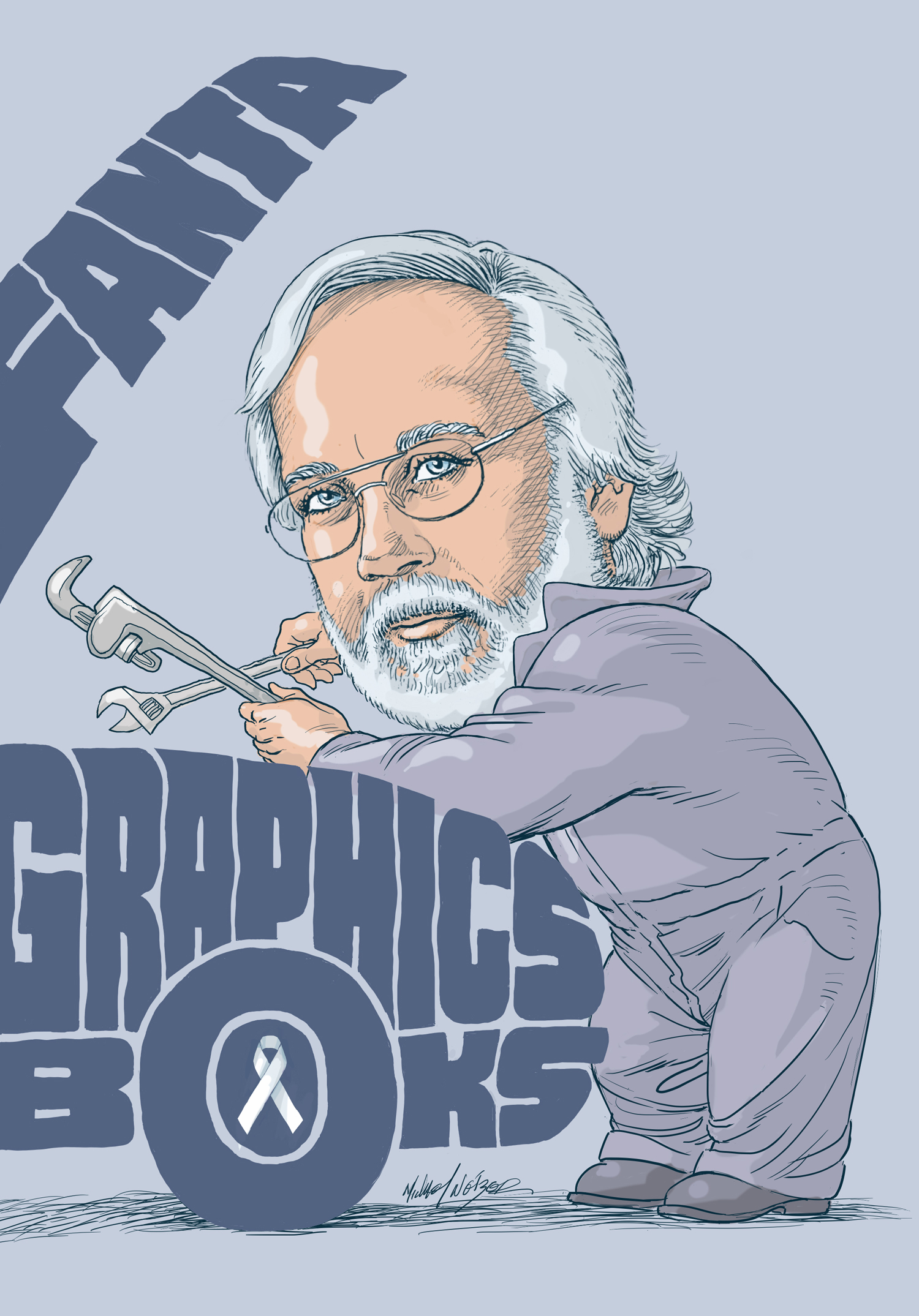

Thompson was a gifted editor, an insightful critic, and a talented translator, but more importantly, he was a towering figure in the world of comics — all the more astonishing for the fact that he did not himself write or draw. He became involved with Fantagraphics when he was only 21 years old, and was with the company, through a series of profound swings of fortune, until his death. It would be fair to say that Fantagraphics would not exist without him — on one level, because of his tireless work in running the day-to-day business of the company, but on another, because he literally rescued it from bankruptcy by sinking his own money into its accounts on more than one occasion. Fantagraphics came by its reputation as America’s finest publisher in the comics medium largely due to his relentless hard work: as a translator of the European comics he grew up loving, as an advocate of publishing new work by great independent writers and artists and rescuing old work by the legends of the medium from falling into obscurity, and as a relentless defender of the right of comics to take their place as legitimate art, as a lively and vital medium second to none. I never got to meet Kim Thompson, but much of his work as an editor and interviewer influenced the way I read and understood comics, and more importantly, almost every book that I came to think of as great art — Love and Rockets, Eightball, Frank, Artbabe, Palestine — as well as the revival of work by R. Crumb, E.C. Segar, Charles Schultz, Walt Kelly, and George Herriman, to name but a handful — bore his thumbprint. Everyone who grew up loving comics in the last four decades owes a debt of gratitude to his tireless work.

Gandolfini seemed like an unlikely figure to make it as an A-list actor, let alone to set off a revolutionary period in the medium of television. His hulking frame, meaty visage, and thick accent seemed destined to mark him as a perennial character player, the filler of bit parts in the credit reel. But when David Chase picked him to play the lead role in The Sopranos for HBO, he became the focal point not only of one of the finest crime dramas ever produced, but of a new era of TV drama that will no doubt be detailed extensively in the eulogies to come. Once his career got rolling, Gandolfini didn’t shy away from playing heavies — a task for which he was both physically and psychically inclined — but he never allowed himself to be typecast. He kept his eye open for work that was rewarding and interesting, and which demanded of him that he slip ever so slightly out of his comfort zone; it was surprising when he turned up as the hard-headed but war-averse General Miller in Armando Ianucci’s savage political satire In the Loop, but it was downright shocking when he showed up in Spike Jonze’s adaptation of the beloved children’s story Where the Wild Things Are. What was no surprise, to those who had followed his career closely, was how well he acquitted himself in both roles. There were low points in his filmography, to be sure, but more than a reliable actor, he avoided the clay-foot syndrome that struck so many of his Sopranos cast members, becoming by most accounts a decent fellow, a supporter of independent film and breast cancer charities, and an advocate of respectful treatment of injured and PSTD-stricken veterans. I never met Gandolfini either, but I wrote a book about the show that made him famous, and that seems enough to feel his death personally.

Perhaps what makes us feel particular deaths so heavily is that on some level, however arbitrarily, we feel a special connection to these people: we share their age, their build, their habits and hobbies, their enthusiasms and aesthetics, even above how much we feel transformed by their work. Whatever the case, in their death, there is, as Dr. Melfi phrased it, “pain and truth”, and we feel a deeper loss for it. Rest in peace, gentlemen.

I’m so glad you mentioned In the Loop; I never saw The Sopranos, so it was this role, in this movie that was kind of a formative experience for me, that I most associate with him. I didn’t expect to see anyone else say anything about it, though.