So, something you might not care about — and why should you, I ask, giving you a chance to bail out now — is the ‘controversy’ over Lupe Fiasco’s new single, “Bitch Bad”. In the song, he attacks the use of misogynistic imagery in hip-hop (the concomitant video compares rap’s aggressive macho posturing to blackface), and questions the influence of stereotypical images of women on young black boys and girls.

That this would cause a lot of controversy is a bit surprising — and even more so, considering the criticism isn’t coming from misogynist rappers. SPIN magazine recently featured not one, but two articles attacking “Bitch Bad” from various angles, some legitimate and some shaky; the vociferousness of it all caused Lupe Fiasco to get to feudin’ with SPIN (a battle he’ll likely win by default, if reports of the magazine’s financial future are to be believed). Meanwhile, over at Ebony, Jamilah Lemieux leaps, if not to LF’s defense, at least to attack the two SPIN writers.

So what’s going on here? There are elements of truth in both arguments. SPIN’s writers are correct in detecting elements of ‘mansplaining’ in the song, and there are arguments to be made that it’s not Lupe Fiasco’s place to be telling black women how to respond to the word ‘bitch’. But Lemieux has an equally good point about how these criticisms are coming from two privileged white dudes who pretend to speak for a perspective they cannot possibly have, and themselves contain more than a few elements of ‘mansplaining’. Lemieux’s argument is stronger and more rigorous; but a number of SPIN’s criticisms hit home.

For me, it took a lot of thinking — almost, gasp!, as if it were a more complex issue than both its detractors and its defenders make it out to be. On the one hand, Lupe Fiasco — who, as Lemieux points out, has a lot bigger profile than other critically praised but lesser-known rappers who have similarly argued against misogyny in hip-hop, and it’s admirable of him to use that bully pulpit to address such a pervasive issue. And, quite frankly, the problem of misogyny in hip-hop is so profound that I’m reluctant to criticize anyone making any kind of stand against it whatsoever.

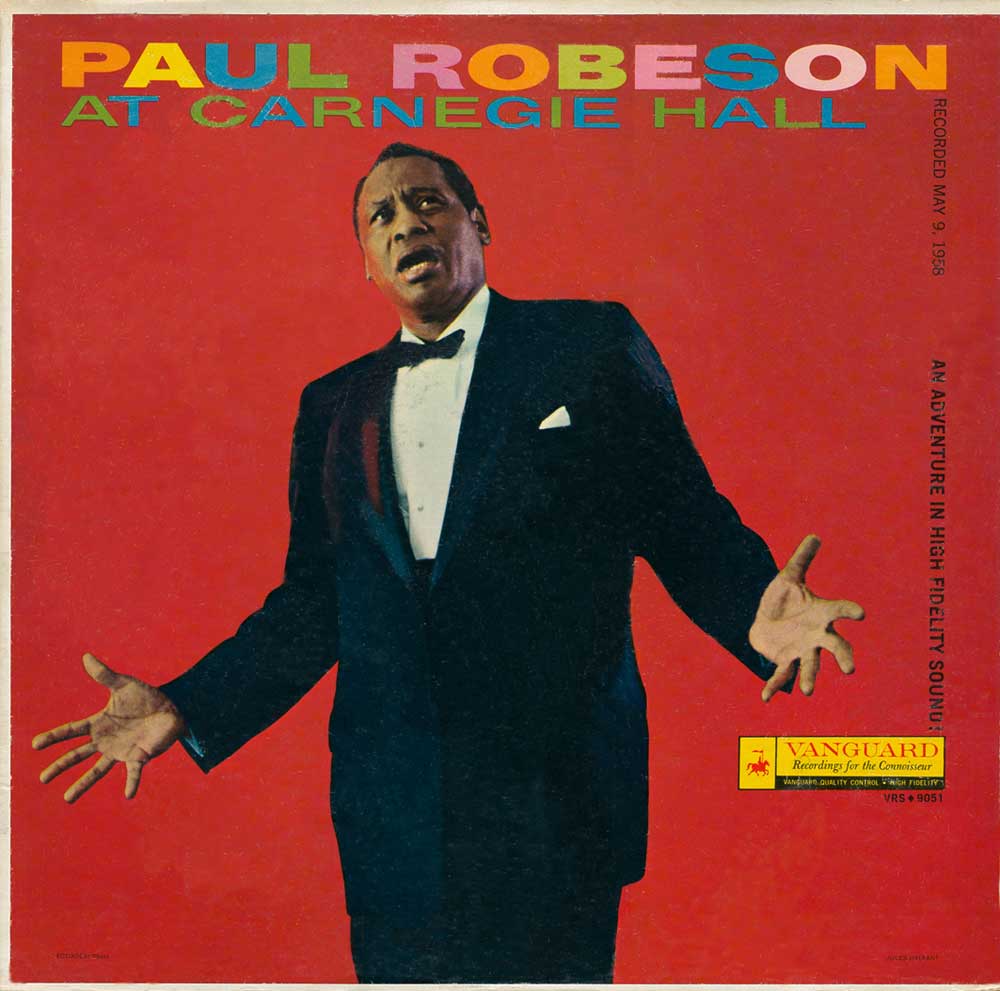

That said, “Bitch Bad” is, well, problematic. Right out of the gate — and stating the obvious (to me, anyway) — the biggest problem it has is that it’s kind of a wack song, lacking any of the charm and flow of Lupe’s earlier work; and following close behind is the overall tone of the song. Political and social consciousness in rap is nothing new, but conscious rap is at its best when it’s righteous instead of preachy. It doesn’t need to be furious to get its message across (see Murs for a fine example of how to deliver the goods with emotion and sincerity without anger), but it also doesn’t benefit from sounding like a lecture. Lupe may be ‘mansplaining’ here because he’s a man, but the hectoring, somewhat condescending tone would sound just as obnoxious coming from a woman. SPIN makes the point that the video is directed by Gil Green, who has lensed plenty of misogynist videos in the past; I think this is a weak criticism, but it leads us to the fact that the video also tries to play it both ways with its depiction of stereotyped black women by attacking the image while also sticking booty right in front of the camera. Whether this is a concession to commercialism or a satirical gesture, it only serves to frustrate the overall intent of the song. Likewise, the comparison of the hard gangsta façade to blackface is clever (if not exactly original), but dedicating the video to Paul Robeson and other performers of the blackface era muddles the message somewhat; couldn’t he have dedicated it to, you know, a woman?

But the real giveaway comes so near the end that you might almost miss it — I’ve seen no mention of it in any of the columns arguing over the issue. Throughout the whole song, the chorus delivers the simple message of its title: “Bitch bad, woman good, lady better”. But in the last iteration, the vocalist closes the circle: “Bitch bad, woman good, lady better — best is motherhood.”

Cue the sad trombone.

Now, okay, I get it. One step at a time, especially in a genre as regressive as hip-hop. We can’t bridge every gap in feminist thinking all at one go. And sure, it’s established early on the song that the role of mothers is important to the message being delivered. But what the song is attempting is to establish that there’s something profoundly wrong about the idea, deeply ingrained in black street culture, that women are bitches; surely someone involved in the creation of this song could have suggested that it does feminism no favors to end it by playing into the equally deeply ingrained idea that the pinnacle achievement of a human female is to bear children? It’s already thorny enough that “Bitch Bad” places “woman” at #2 on a hierarchy of femininity, just above “bitch” but below “lady” — you know, a classy female, not like those ordinary women — but to end it with a reminder that if you really want to be a worthwhile female, you’d better get to having children is far and away the biggest speed bump on this road of good intentions.

I don’t want to start beef with Lupe Fiasco (like he’s ever going to read this); I generally like his stuff, I’ve followed his career since it began, and I wish him success. I’m not interesting in bringing him down; it seems to me that he’s clearly on the side of the angels on this one, as is anyone else who takes the opportunity to address sexism in hip-hop. But enlightenment is a journey, and he’s acting like he’s already reached the destination; when the biggest argument against your own position comes from you, maybe you’ve still got a ways to go. Many of the criticisms of SPIN’s attack on “Bitch Bad” are dead on, but we shouldn’t pretend that the song, and the ideas behind it, are any kind of feminist manifesto. Lupe wants to put hip-hop’s house in order, and that’s admirable. But so far, he’s only tidying up, and he’s swept one of the biggest messes rather obviously under the rug.